Cornell radiologist develops advanced atlases of animal brains

Dr. Philippa Johnson knows her way around brains. A clinical radiologist and diplomate of the European College of Veterinary Diagnostic Imaging, she specializes in advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques. Now she has mapped out her findings in three brain atlases — equine, canine and feline — to help guide colleagues to better diagnostics in veterinary medicine.

“Currently, our state of neuroimaging is to perform standard MRIs,” said Johnson, who joined CVM’s department of clinical sciences as an assistant professor four years ago. “But there are limitations, because readouts can be variable between radiologists, and some of the lesions — such as in epilepsy —aren’t visible on standard MRIs. The diagnosis is therefore presumptive. So, I wanted to start applying the most advanced forms of neuroimaging currently being done in human clinical research in the veterinary world. The big tool that we were missing was the brain atlas.”

Cutting-edge, high-resolution, so-called stereotaxic brain atlases bring data obtained from multiple individuals into a standardized virtual space. “There they can be compared to each other,” Johnson said. “The atlas also enables us to identify a standardized region in the brain that we want to compare across subjects.” She hopes that the newest publications — freely available for download online — will enhance the few existing tools and fill in significant gaps.

Take the equine brain, which had not yet been mapped. Supported by the Harry M. Zweig Memorial Fund for Equine Research, Johnson and her colleagues used powerful 3-Tesla magnets with twice the power of routine MRI devices to image the brains of 15 horses euthanized for reasons unrelated to the study. They averaged the measurements of 10 horses to create a generalized model and used the remaining five to test whether, when brains are registered to — or integrated into — the atlas, the data quality is maintained (a process called “validation”). The team also made sure to equip the equine brain atlas with subcortical masks, a feature that lets users separate out specific parts of the brain for more detailed insights.

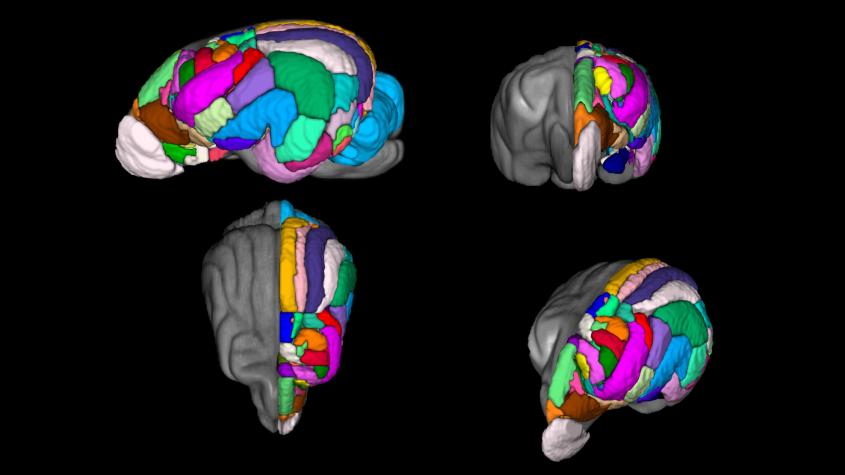

Until recently, such cortical gray matter masks were missing from all existing brain atlases for dogs, who — as close partners to humans, with long life spans and many similar health issues — have frequently served as models for human disease. To fill in the gap, Johnson and her team, in collaboration with University of Sydney ophthalmologists Drs. Kathleen Graham and Andrew White, collated data from 40 dogs. They divided their new atlas into 234 regions, based on intricate drawings of the brain’s myeloarchitectonics — segmentation of the cortex according to the cellular architecture or the tissue — by Polish anatomist Jerzy Kreiner. “Each region is likely to have a specific function, but at this stage we don’t know yet what these are,” Johnson said. “We’re going to understand more as we do more functional imaging of the canine brain.”

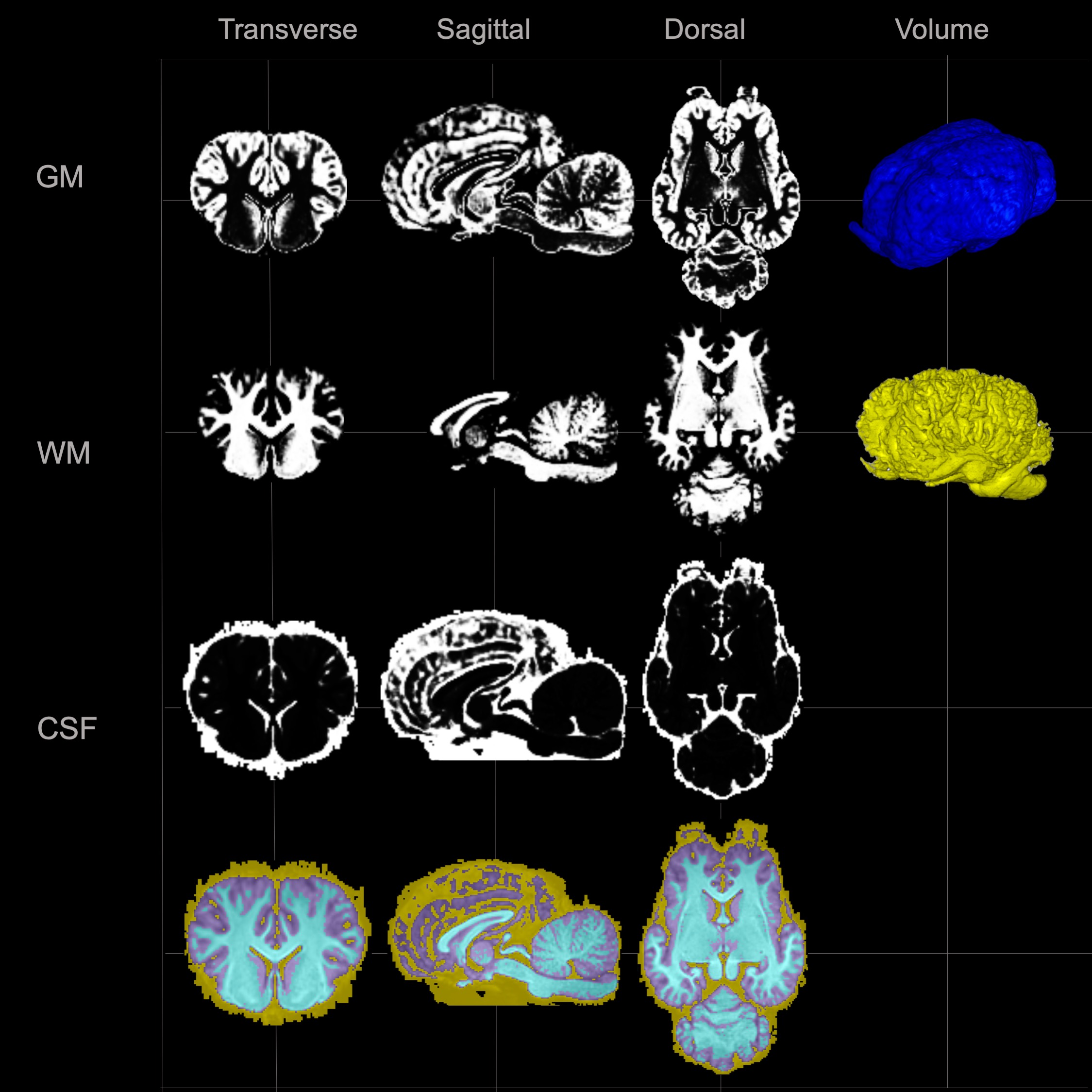

While Johnson considers the canine cortical atlas to be the strongest available in the current literature, additional layers are already in the works. The gray matter mapped so far is “where all the thinking happens,” she said. Now, the team has shifted its focus to white matter, which transports the messages to different parts of the brain or down the spinal cord. Johnson and her colleagues are mapping major white matter pathways using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), an advanced MRI technique that detects different forms of water diffusion in tissue and can be used to virtually dissect white matter with the help of tractography, a 3D-modeling process.

DTI tractography also produced the most recent feline brain atlas that Johnson published in mid-March. Users can compare cats’ brain scans to the atlas to pinpoint which regions show changes with certain diseases. “We can see, for instance, which pathways are affected by feline aging,” Johnson explained. “Or, say, I have a group of feline epilepsy cats, and all of them have these changes within their brain over this specific region of white matter. What region is that?”

While Johnson would have preferred to work with data from more than eight cats for the feline atlas —human brain templates may be created from as many as 250 individuals — feedback from colleagues around the world has been positive. “Each manuscript has its own specific purpose, and they can always be improved on,” she said. “Our lab really welcomes collaboration and data sharing, so we’re very open to different labs reaching out to us. It’s nice to be able to support the application of advanced MRI techniques in veterinary neurology, and we’d like to promote this level of research as much as possible.”

-By Olivia Hall