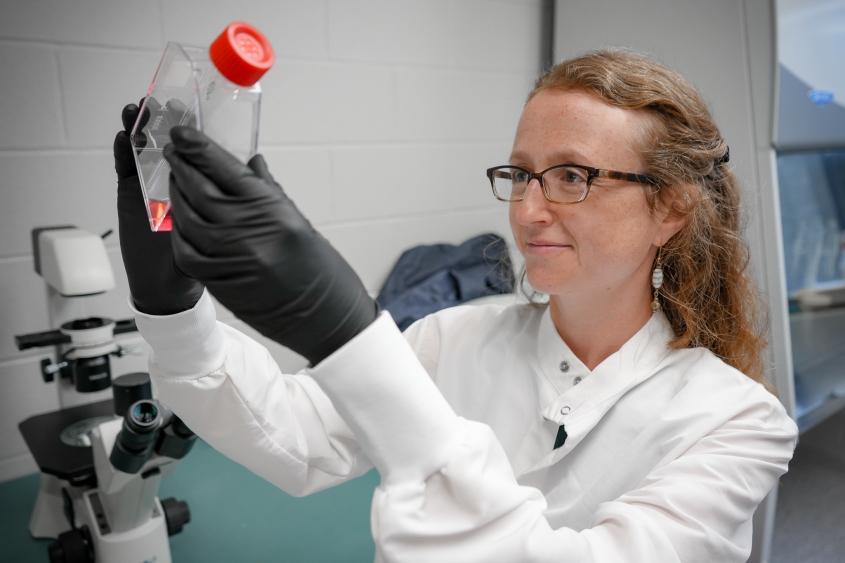

Virologist Sarah Caddy builds on the Baker Institute’s 75-year history of groundbreaking research

Every time Dr. Sarah Caddy drives to her lab at the Baker Institute for Animal Health, she passes by Parvo Drive, immediately adjacent to the building. It’s a fitting welcome. Not only does the assistant professor at the Baker Institute for Animal Health in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology conduct cutting-edge research on viruses, but she does so continuing along the institute’s 75-year, storied path of innovative collaborative research and pioneering discoveries.

“It is exciting to work in a place that is so rich in veterinary research history,” Caddy said. “I always enjoy having visitors and telling them stories of the things that have been uncovered in this very institute.”

Since Caddy arrived in Ithaca from her native U.K. in 2022, much of her lab’s focus has been on understanding how antibodies work against viruses. “A lot is still not known about how these incredible little proteins work, even though they are pivotal to protecting animals – including humans - from different virus infections,” she said. She is especially interested in maternal antibodies, which are passed from mother to infant through the placenta or milk in all mammalian species. During the very high-risk period following birth, these antibodies provide essential protection to babies whose own immune systems are immature and not ready to combat the microbes that might otherwise infect them.

Working across species and viruses

Caddy, who earned her veterinary degree from the University of Cambridge, studies this topic in multiple species – including in dogs, horses, and humans. Funding from the Wellcome Trust has allowed her to start investigating a serious problem that interferes with the protection of babies by vaccines against rotavirus, a major cause of vomiting and diarrhea. That vaccine has been seen to be significantly less effective in protecting babies in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) compared to the protection seen in the United States, where up to 95 percent of babies are protected. The Caddy lab is now working with partners in Vietnam and Zambia to study serum samples from vaccinated children, and their results then become part of a large repository for comparison and analysis.

One of the reasons for the lower effectiveness of the vaccine in LMICs includes the fact that mothers are exposed to more infectious diseases, Caddy explained. In response, their immune systems produce more antibodies, which are passed on to their children. “As a result, the vaccines often don’t work as well as they should because those maternal antibodies can block infant immune responses to the vaccine,” she said. “In that way, maternal antibodies are a double-edged sword, and we’re really just starting to understand how the biology behind this works.”

Caddy’s Ph.D. in virology from Imperial College London makes her uniquely qualified to also apply herself to this question with studies in dogs – the second major branch of her lab’s research. “And this is where the legacy of the Baker Institute really comes into play,” she said.

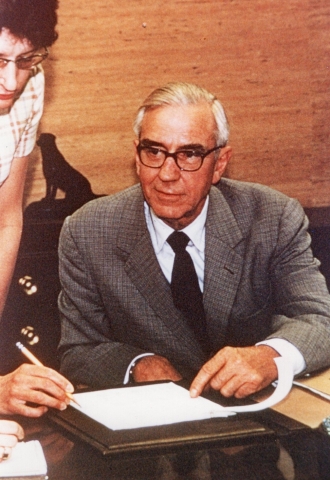

Research with deep roots at Baker

In 1958, Dr. James A. Baker, Ph.D. ’38, D.V.M. ’40, the institute’s founding director was a co-author on one of the first published papers confirming that antibodies were transferred from dogs to their puppies. In this study, the antibodies protected puppies against canine distemper virus, at that time a common deadly disease. This discovery came only a few years after the Cornell Research Laboratory for Diseases of Dogs had been dedicated, in 1951, as a division of the newly founded Veterinary Virus Research Institute, later to be renamed in Baker’s honor.

The researchers noted a finding directly relevant to Caddy’s research today: Puppies could not develop immunity from a vaccine until they had lost the protection conveyed from their mother and become susceptible to the deadly distemper virus infection. But when would be the right time to vaccinate? Based on the consistent decline of maternal immunity as the puppies grow, Baker and his colleagues developed a helpful nomograph (a two-dimensional diagram). It permitted, they wrote, “on the basis of the serum titer shown by the pregnant dog, a prediction of the age at which puppies as yet unborn could be immunized and thereby make available maximum protection from vaccine by vaccination at the earliest possible age.”

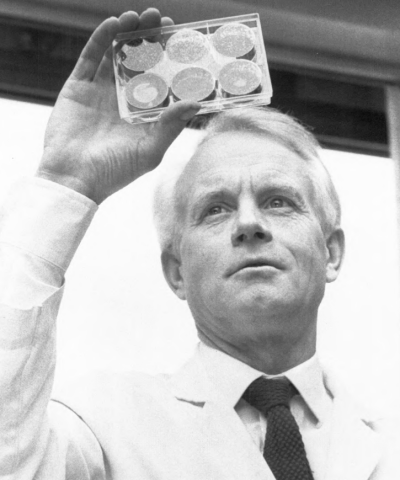

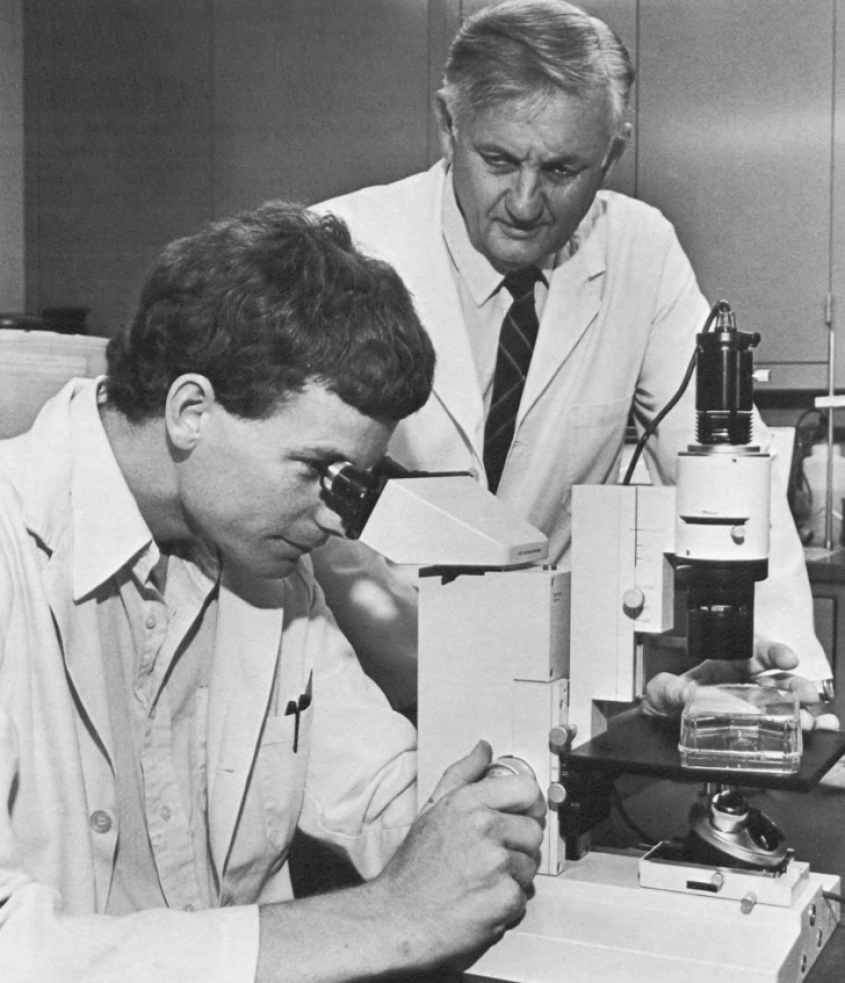

Subsequent work by Leland “Skip” Carmichael, D.V.M., Ph.D. ’59 – one of Baker’s first graduate students and later the John M. Olin Professor of Virology – and others showed that the vaccine for measles used in humans could be used to immunize young puppies against distemper virus. Because the measles virus was related to distemper but slightly different, it was more effective in pups who still had enough antibody to interfere with the distemper vaccine itself, said Roy Pollock, D.V.M. ’78, Ph.D. ’81, one of Carmichael’s advisees and now chief learning officer at The 6Ds Company. “That is now standard practice and has saved thousands up thousands of puppies from death due to distemper,” he explained.

In 1978, Pollock would team up with Carmichael and virologist Max Appel, Ph.D. ’67, now professor emeritus, to meet a new challenge confronting the canine world – a rapidly spreading disease that caused vomiting, severe diarrhea and death. Thanks to the Baker Institute’s unique location, state-of-the-art facilities and faculty expertise, Pollock recounted, they were able to make quick headway in identifying parvovirus as a never-before-seen virus in dogs. Within three years, they had followed up with a diagnostic test (which remained the standard for many years), a vaccine – and a seminal 1982 paper.

“It was still very soon after the discovery of canine parvovirus and there was much to learn about the transmission, pathophysiology, and development of immunity, both natural and by immunization,” Pollock said. He and co-author Carmichael showed that for parvovirus, antibodies alone were sufficient to fully protect puppies, and they showed that once a dog had been infected, it remained immune for many years; and also that mothers passed on their immunity to their pups.

As in Baker’s earlier work on distemper, maternal immunity was seen to be effective in protecting puppies from canine parvovirus for the first 8 to 12 weeks of life, but they also blocked successful vaccination. “Since you could not be sure when any individual pup would respond to vaccination, the solution was a series of shots to catch those with low immunity early but also be sure there was one late enough to vaccinate those with higher levels – and therefore longer-lasting – maternal antibodies,” Pollock explained.

To this day, parvovirus has remained in the crosshairs of Baker Institute faculty. Colin Parrish, Ph.D. ’84, the current John M. Olin Professor of Virology, completed his graduate work with Carmichael and went on to identify the cause of the pandemic: a mutant version of the feline panleukopenia virus that emerged in dogs as the first canine parvovirus. ”Our work has shown that the canine parvovirus in the 1970s emerged as a variant of a virus of cats – feline panleukopenia virus – and spread as a pandemic in dogs during 1978. We have shown that dogs were able to be infected because the virus gained the ability to bind and infect the cells of dogs, and that it continues to evolve in both cats and dogs to create variants with altered properties” Parrish said.

Continuing down the path of excellence

Now Caddy has taken up the baton to continue the Baker Institute’s long history of research on canine viruses and the role of maternal immunity.

While it has long been known that most maternal antibodies in dogs are transferred shortly after birth through the colostrum, some are also transferred through the placenta before birth. With funding from the Riney Canine Health Center, Caddy’s team is collecting samples during canine cesarian sections at the Cornell University Hospital for Animals to examine the role of maternal antibodies transferred through the placenta. Comparing titers from the mother and from the puppy’s cord blood, “we’ve already found some interesting differences in the biology,” Caddy said. They have found that about five percent of the maternal antibodies pass through the placenta, compared to nearly a hundred percent in humans.

In future work, Caddy hopes to take a closer look at the role of the placental transfer in dogs to understand the source of some of these differences. “We’re really hoping to take it a step further to understand the actual biology underpinning this transfer,” Caddy said. “And once we know more about it, can we enhance it?”

Caddy is well aware of the scientific heritage upon which she is building. “We’re building on work that Skip Carmichael and James Baker did,” she said, now studying a diverse population of client-owned dogs. “It’s wonderful to be continuing and extending that research by using a new array of antibody tests that examine all aspects of antibody structure and function.”

Caddy is similarly appreciative of the lineage of Baker scientists she became part of when, in 2007, she spent a summer dipping her toes into virology in the lab of associate professor of virology John Parker, Ph.D. ’99 as part of Cornell’s Veterinary Investigation and Leadership Program. (Parker was also Parrish’s graduate student.) The experience inspired her to pursue a Ph.D., and when her current position at the Baker Institute became available, “everything came together to make sense for what I wanted to do with my career,” she said.

“We’re a unique institution, and I appreciate the opportunity to cover all species, from pets to humans, from domestic animals down to mice,” Caddy said. Even more, “we’re a lovely little and very productive community up on the hill” – one that she hopes to continue to grow. Two summer leadership students have already trained at her lab. “It’s a real pleasure to continue that cycle,” Caddy said.

Article written by Olivia Hall