Rabies or Canine Distemper?

For the past four years, the Animal Health Diagnostic Center has partnered with the New York State Department of Conservation to develop a statewide wildlife health program. The program focuses on wildlife disease surveillance as well as research, staff training and support of policy initiatives. Wildlife cases are regularly submitted to the AHDC for necropsy and diagnostic testing, and epidemiologic data are collected for analysis on each case.

In February of this year, a neurologic raccoon was euthanized and submitted to the AHDC by a wildlife rehabilitator. The rehabilitator described the animal as obtunded and salivating, and rabies was the primary differential diagnosis.

On gross necropsy the animal was given a body condition score of 5/9 (good). The corneas were cloudy. Both the left cranial and left caudal lung lobes were collapsed and slightly firm. A small amount of pulmonary edema fluid was noted in the trachea and bronchi.

A brain sample was submitted for Rabies FA, and lung and bladder were submitted for canine distemper PCR and FA. Rabies testing was negative, while the canine distemper FA and PCR were both positive.

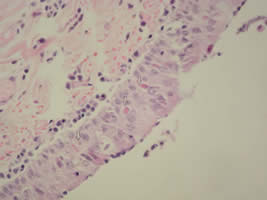

Histopathology confirmed pulmonary edema and enteritis consistent with distemper, although no inclusion bodies were seen and IHC on the lung samples was negative. Nephritis typical of leptospirosis was identified on sections of the kidney, and an immunohistochemistry with a modified Steiner silver stain confirmed the presence of classic spiral bacteria within tubules. In sections of the brain numerous intralesional protozoal cysts were associated with multifocal meningoencephalitis. IHC on the brain for toxoplasma and neospora was negative. Sarcocystis neurona was confirmed by PCR.

Canine Distemper circulates seasonally in wildlife species including skunks, raccoons and grey foxes, with a bimodal distribution in the spring and fall. Since the confirmed case in this raccoon, we have received eight other cases this spring from counties around New York. Interestingly, there has never been a confirmed clinical case in red foxes (which are a different genus than grey fox). Canine Distemper is also known to infect large exotic cats and mustelids including domestic ferrets. Routine vaccination can prevent infection in susceptible species. The standard modified live canine vaccine is known to cause clinical disease in ferrets and grey fox, so a recombinant distemper vaccine is recommended for all exotic species.

Multiple tests are available at the AHDC for Canine Distemper diagnosis, including FA, PCR, serology and IHC. Most of our diagnostic tests have not been formally validated for use in wildlife, and so may be less sensitive or specific than when used in domestic animals; this should be taken into account when interpreting test results. We frequently choose FA for initial screening because it provides the most rapid diagnosis (usually results are available within 24-48 hours). In most species, the most sensitive tissues for post-mortem distemper testing include lung, bladder, brain and foot pads. Antibodies may take a week or so to develop, so serology can be useful for diagnosis when an animal has had a more prolonged course of infection.

Distemper shedding can continue from 60-90 days post infection. The virus is not very stable in the environment when exposed to heat or sunlight and will only survive for a few hours. However in cool, dark and damp areas the virus may persist for days to weeks. It is very susceptible to disinfectants that are phenolic compounds (ex. Pheno-Tek) and quaternary ammonium compounds (ex. Rocal). A bleach-water solution may also be used for disinfection.

This particular case illustrates that distemper and rabies infections may be indistinguishable in wildlife species, and testing for both diseases should be considered for susceptible species. This animal had simultaneous infections with two additional agents (Sarcocystis and Leptospirosis), and we were not able to determine how these diseases interacted in the death of this animal.