Oncology

The oncology service at the Cornell University Hospital for Animals offers comprehensive consultation, diagnostic services, staging and treatment plans for all cancers of companion animals. We have faculty members and residents-in-training who collaborate with specialists throughout Cornell to provide comprehensive care for your pet.

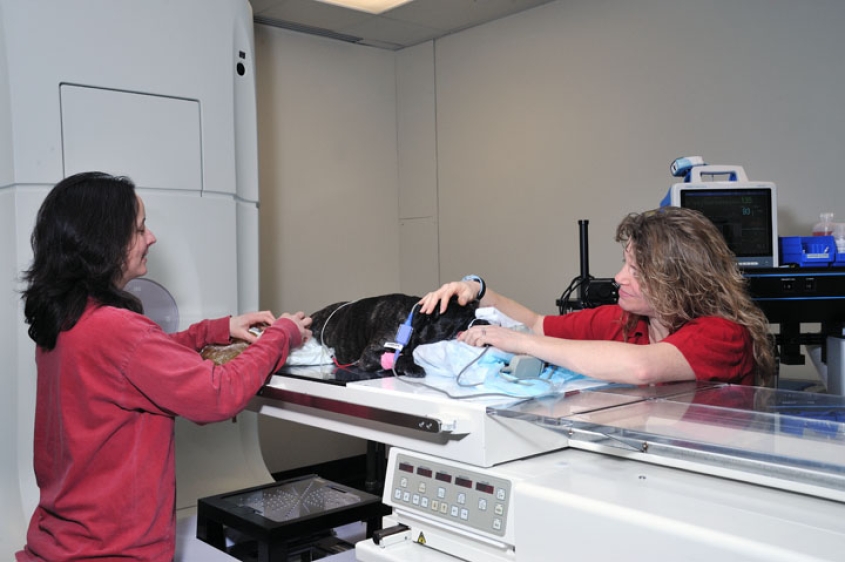

We offer a wide range of advanced diagnostic techniques and provide the most comprehensive cancer treatment available. Our technicians are experienced in treating oncology patients and are trained specifically in the administration of chemotherapy and the delivery of radiation therapy. We will work with your primary care veterinarian to conduct diagnostic tests, create treatment plans and administer medical, radiation or surgical treatments tailored for your pet's condition.

Additional Information

Advanced Techniques

- Technicians experienced and trained specifically in the administration of chemotherapy

- Intravenous, intralesional and intracavitary chemotherapy administration

- Technicians trained specifically in the administration of anesthesia

- Ultrasound guided and manual tru-cut biopsies

- Bone marrow aspirates

- Melanoma vaccine administration

- Incisional and punch biopsies

- Long infusion chemotherapy administration (such as Cisplatin, Ifosfamide, and Cytosar)

- Palliative care/pain management with Pamidronate and Ketamine/Lidocaine infusions, radiation therapy and oral pain medications

- Access to multiple specialties for complete diagnostics, staging, treatment planning and monitoring including Computed Tomography, MRI, Radiology, Ultrasound, Surgery, Clinical Pathology and Histology

- External Beam radiation therapy with a 6MV linear accelerator with 6 different electron energies ranging from 5-14 MeV

- Strontium Radiation treatment therapy

Oncology: Medical Conditions

Lymphoma

Lymphoma, a cancer of white blood cells, is one of the most common cancers of dogs and cats. It can arise in lymph nodes as well as organs such as the spleen, liver, intestinal tract and skin. In dogs, the most common presentation is non-painful enlargement of the body’s lymph nodes - typically under the jaw, in front of the shoulders and behind the knees. The most common location of lymphoma in cats is the gastrointestinal tract. The symptoms vary depending on what organs are involved, and can include decreased appetite and energy level, vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, and increased drinking and urination.

Diagnosing lymphoma usually starts by obtaining cells of the affected organ with a needle for a clinical pathologist to examine. This can be done quickly, rarely needs anesthesia and results are usually back within 24 hours. If the results are suggestive of lymphoma, a larger portion of the lymph node or organ involved will be taken and sent to the histopathology lab for analysis. Many times this can be performed while the patient is under a short-acting anesthetic. However, if the intestinal tract is involved, samples may need to be obtained through endoscopic or surgical biopsy. The pathologist can tell from the biopsy if the lymphoma is high grade or low grade – this will help us determine the type of chemotherapy that will be most effective. We can also determine if the lymphoma is a B cell or T cell lymphoma, which helps to predict prognosis. Other staging tests will be performed to look for other affected organs. This includes a complete blood cell count, chemistry profile, urine analysis, chest x-rays, abdominal ultrasound, and bone marrow aspirate. The results of these tests will help us evaluate the extent of the disease and normal organ function. This allows us to determine prognosis and how well a patient may handle chemotherapy.

Lymphoma is treated with chemotherapy. Although we cannot cure lymphoma, we can get up to 90 percent of dogs and 65 percent of cats into remission with a multidrug chemotherapy protocol. A complete remission means all signs of the cancer are gone. Most multidrug chemotherapy protocols for lymphoma last 6 months, and are given weekly for the first few months then the interval between treatments increases. For dogs and cats in remission at 6 months, chemotherapy is discontinued and patients are rechecked monthly for signs of recurrence. When the patient comes out of remission, chemotherapy can be restarted. However, the duration of the second and subsequent remissions is often shorter.

There are other treatment options available that require less frequent visits and may be less expensive. These protocols typically result in a shorter survival time compared with a multidrug chemotherapy protocol.

Dogs and cats with high grade lymphoma without treatment usually live for only four to six weeks. (Shorter and longer times are possible.) Dogs treated with a multi-drug chemotherapy protocol have a median survival time of one year with 25 percent of dogs living to 2 years. Cats treated with a multidrug chemotherapy protocol have a median survival time of 7 months; however some cats that achieve complete remission can live longer.

Low-grade small cell lymphoma of the intestinal tract in cats is a less aggressive form of lymphoma. Symptoms include chronic vomiting, diarrhea, weight loss, and/or decreased appetite. This type of lymphoma is often treated with an oral chemotherapy agent that is administered by the owner at home. The prognosis for is generally good with survival time being 2 years or more in many instances.

Canine Mast Cell Tumors

Mast cell tumors are the most common malignant skin tumor in dogs. Mast cell tumors vary in appearance and can be found on the skin or can be subcutaneous. They can look like lots of different non-cancerous skin tumors (particularly lipoma for mast cell tumors that are subcutaneous), so it is important to have all lumps and bumps located on or under the skin evaluated by a veterinarian.

Mast cell tumors are usually diagnosed by fine needle aspirate - collecting cells with a small needle and spreading them on a microscope slide. Mast cells are quite distinctive under the microscope as they have purple granules inside the cell. These granules contain substances involved in inflammation such as histamine and heparin, which may cause your dog’s tumor to change size or look bruised, or cause your dog to scratch at it. Once we know your dog has a mast cell tumor, we need to know whether or not it has spread, or metastasized. When mast cell tumors spread they tend to go to the area lymph nodes.

A fine needle aspirate (similar to aspirating the primary tumor) or a biopsy is recommended to see if there are cancerous mast cells in the lymph node. Sometimes, we may need to use ultrasound to visualize the lymph node. Once a mast cell tumor has spread to the lymph node, it may also spread to the spleen, liver, and bone marrow. Additional tests such as an abdominal ultrasound and bone marrow aspirate may be recommended.

Treatment for mast cell tumors includes surgery, radiation therapy, and chemotherapy. The choice of treatment will depend on the size and location of the tumor, as well as the grade of the tumor. The grade of the tumor is determined by the pathologist after biopsy or surgical removal. There are three grades: Grade I tumors are easily identified and rarely metastasize; Grade II tumors have intermediate differentiation and extend deeper into the underlying tissues and about 20 percent will spread or metastasize; Grade III tumors are poorly differentiated and behave aggressively with an 80 percent or higher chance of metastasis.

Surgery is the treatment of choice for mast cell tumors. Incompletely removed tumors can be treated with a course of radiation therapy for excellent long term control. Chemotherapy is often recommended for dogs with a tumor that is too large to remove surgically, has spread to a lymph node, spread to other places or is a Grade III tumor with a high likelihood of metastasis.

The prognosis for dogs with mast cell tumors is variable. Many tumors can be removed surgically and cured. Dogs that have had one mast cell tumor in their life are at risk for developing another mast cell tumor, so careful monitoring is recommended. Prognosis depends on the size of the tumor, the grade of the tumor and whether or not it has metastasized.

Canine Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcoma (OSA) is the most common primary bone tumor, and accounts for more than 85 percent of malignant bone tumors in dogs. Bone tumors can both produce bone and destroy the normal bone tissue. The median age of onset is 7 to10 years (with a second early peak at 1 to 2 years), with large and giant breed dogs having an increased incidence. Breeds at increased risk include Saint Bernard, Great Dane, Scottish Deerhound, Irish Setter, Doberman pinscher, Rottweiler, German Shepherd, and Golden Retriever. There is no consistent gender predilection.

Pain is the most common clinical sign of bone tumors, and dogs are usually progressively lame and may have swelling at the primary site. There may be an association with recent mild trauma. The duration of signs can range from days to months.

The diagnosis is made based on history, x-rays of the bone and ultimately a biopsy, or removal of a tissue sample from the tumor.

Osteosarcoma commonly spreads to the lungs, and less commonly spreads to other bones and organs. The treatment usually involves surgery - often amputation - to remove the painful tumor followed by chemotherapy to slow down the spread of the cancer. The majority of dogs have metastasis at the time of diagnosis, but few will have radiographic evidence of spread to the lung. Palliative options are also available including radiation therapy and intravenous drug protocols to provide pain relief.

Median survival time with surgery alone or palliative radiation therapy is 4 to 5 months. Median survival time with surgery and chemotherapy ranges from 7 to 12 months.

Feline Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma

Oral squamous cell carcinoma is the most common cancer of the mouth of cats. It is usually found in older cats with an average age of 12.5 years. It can originate under the tongue or involve the gums. The most frequent sign associated with this type of cancer is a decreased appetite or difficulty eating. You may also notice bad breath, increased salivation or drooling or a swelling of the upper or lower jaw. It can invade the bones of the jaw and be painful.

Squamous cell carcinoma is diagnosed by biopsy. Although rare, it can metastasize to the regional lymph nodes and lungs, so a fine needle aspirate of the lymph node and chest X-rays are recommended. Dental radiographs or a CT scan may be recommended to determine if there is invasion into the underlying bone and whether or not surgery can be done, and the extent of surgery required.

Unfortunately due to the location and invasive growth pattern, squamous cell carcinoma cannot be surgically removed unless detected very early. Treatment often consists of palliative care including radiation therapy (with or without chemotherapy), pain medications and local nerve blocks.

Prognosis for cats with oral squamous cell carcinoma is poor with survival times usually ranging from 2 to 6 months. When detected early and treated with a combination of surgery and radiation therapy, survival time can be significantly prolonged.

Canine Hemangiosarcoma

Hemangiosarcoma is a cancer of endothelial cells – the cells that line blood vessels. The most common sites for this tumor in dogs are the spleen, heart, and skin; however, it can occasionally be found in other organs. Symptoms occur because the tumors are filled with blood and can easily rupture and result in internal bleeding. When the tumor is located in the spleen or heart, signs initially can be vague – decreased appetite, lethargy or weakness, pale gums, collapse, distended abdomen, difficulty breathing and weight loss. Signs can wax and wane over time. In some instances hemangiosarcoma can cause sudden death due to tumor rupture and internal bleeding.

A diagnosis is made based on history, physical examination findings and other diagnostic tests. An abdominal ultrasound and chest x-rays are recommended to assess the extent of disease. Fine needle aspirates or obtaining a sample of fluid from the abdomen or around the heart may be necessary to evaluate the patient. Additional tests typically include a complete blood count, chemistry panel and coagulation profile.

Treatment for splenic hemangiosarcoma consists of removing the spleen. Emergency surgery may be required if the tumor has ruptured, and the patient is bleeding into their abdomen.

Treatment for hemangiosarcoma of the heart is more challenging. Surgery may be possible in some cases, but not all. Because these tumors have a tendency to bleed, blood accumulates between the heart and the pericardial sac surrounding the heart, causing the heart to function poorly. Removing the pericardial sac can allow the fluid to be released into the chest cavity and relieve the pressure on the heart.

Survival time with surgery alone for tumors of the spleen and heart is around 3 months. With the addition of chemotherapy survival time is around 6-8 months. Shorter and longer times are possible.

What to Expect During Your Appointment

Your scheduled visit to the Oncology Service at the Cornell University Hospital for Animals begins with check-in at the reception desk. Following a small amount of paperwork, you will be greeted in the waiting room by one or two veterinary students currently in their oncology clinical rotation, and brought to a private examination room.

The students will inquire about your pet's history. They may perform a physical examination of your pet, an invaluable experience for their education and development. We appreciate your patience and understanding in allowing these future veterinarians to interact with you and your pet.

The students will then leave to consult with a resident and faculty member about the history, physical examination and recommendations for case management. The faculty member or resident will accompany the student back to the examination room to examine your pet again and discuss the diagnosis, next steps, cost and logistics.

Often, you will be asked to leave your pet in the care of our students and clinicians so that we can begin appropriate testing, which can include blood tests and imaging studies. Given the schedule and potential need for consultations with other specialists regarding your pet's care, you may be asked to return to discuss our findings later in the day. Some animals with more serious conditions will be admitted to the hospital for further monitoring and treatment.

Success Stories

Bruzer

Bruzer is a playful, three-year-old Boxer-Mastiff mix. His owners first noticed he was sick in the summer of 2011 when he stopped eating. Bruzer's primary care veterinarian treated him for hypercalcemia (high blood calcium) and renal failure. When Bruzer's condition did not improve, his primary care veterinarian referred him to the Cornell University Hospital for Animals.

After an extensive diagnostic work up, Bruzer was diagnosed with Stage Vb T cell lymphoma. He initially spent six days in the hospital before he was stable enough to be discharged, but left the hospital with a guarded prognosis.

Following his hospital stay, Bruzer was treated with a six-month protocol of chemotherapy, fluid treatments and medicine for kidney failure.

Through the dedication of Bruzer’s family, the veterinarians at CUHA and his primary care veterinarian, Bruzer has achieved 10 months of remission of his cancer, and passed the 1-year anniversary since his diagnosis. He still struggles with the damage the hypercalcemia did to his kidneys, but he continues to enjoy life to the fullest.

"Working with the veterinarians and staff of Cornell has been wonderful," said Jim Miller, Bruzer's owner. "The oncology department took exceptional care of him and made us feel comfortable even though we were dealing with a very difficult situation. We have been able to enjoy Bruzer for a year longer than we expected to have him, and that means so much to us."

Related Info

American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine

An organization responsible for establishing training requirements, evaluating and accrediting residency training programs, and examining and certifying veterinarians in the veterinary specialties of Cardiology, Oncology, Neurology, Large Animal Internal Medicine, and Small Animal Internal Medicine.

American College of Veterinary Radiology

An organization of veterinary specialists dedicated to the highest quality of service in diagnostic imaging and radiation oncology, to optimize veterinary patient care, and to advance the science of veterinary radiology and radiation oncology through research and education.

Veterinary Cancer Society

A professional veterinary organization dedicated to veterinary oncology that includes specialists in medical, surgical, and radiation oncology, internists, pathologists, pharmacologists and general practitioners worldwide.