Multi-disciplinary team at Cornell diagnoses and treats dog’s rare, dangerous pregnancy complication

First Lady, an Australian labradoodle, recently survived a life-threatening pregnancy complication never before reported in dogs. Thanks to the fast action of the emergency and critical care service at the Cornell University Hospital for Animals, veterinarians in the theriogenology department made the diagnosis and performed the surgery that put the labradoodle on the road to recovery.

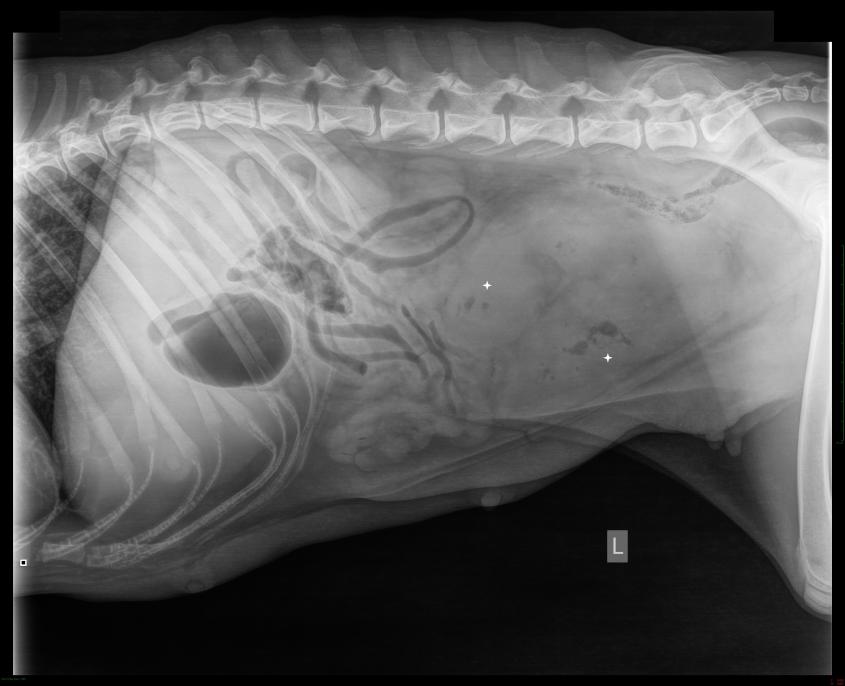

The three-year-old dog became lethargic and feverish after a long labor that produced seven pups. The breeder’s kennel manager brought her to the hospital. Dr. Brittany Zumbo, a small-animal rotating intern at Cornell, determined the dog had a post-partum uterine infection, not uncommon in dogs within two weeks of labor. What was unusual was how very sick this dog was. Upon X-ray and ultrasound, Zumbo saw gas in the uterus. This raised concern about bacterial fermentation, a sign of infection, so she called the department of theriogenology for a consult.

Dr. Mariana Diel de Amorim, faculty member in the theriogenology department, also was concerned about potential for placenta percreta as well as impending uterine rupture. The emergency and surgical teams discussed options and stabilized the dog overnight. Further diagnostic imaging showed fluid around the uterus, affirming the suspected uterine rupture, and the subsequent need for surgery. Dominick Valenzano, D.V.M. ’15, third-year small animal surgery resident, managed the surgery and post-op. He found areas of perforation where infected fluid was leaking from the uterus and submitted tissue samples from these lesions for micro-analysis.

“The cells of the placenta were invading the uterus from the endometrium (inner layer) to the outer most layer. This is a condition on the placenta accreta spectrum, and this dog had the most severe form,” explains Dr. Lacey Rosenberg, a theriogenology resident who also worked the case. Cornell reproductive pathologists then helped identify and confirm the specific diagnosis of placenta percreta, noting that this condition, while diagnosed occasionally in humans, has never been reported in a dog.

While no prior knowledge of this condition exists in dogs, the Cornell team theorize that the placenta’s invasion of the uterine wall weakened the uterine muscle, causing weaker contractions and extending labor, which in turn increased the risk of bacterial infection into the uterus. They also believe the uterus ruptured due to the weakened areas of placental invasion. The kennel manager did not see the placenta pass after labor, so the team also considered that the tissue left behind became infected.

This never-before-seen case is now the subject of a case report written by Rosenberg, who hopes to have published. She also will present the case this summer at the Society for Theriogenology Conference.

The dog was spayed and her puppies were divided between two other of the breeder’s female dogs who had recently had litters. This gave First Lady the time and ability to heal, while also making sure the puppies could thrive.

“It was a good outcome for everyone. The puppies were nursed and are doing great, and she returned home to a loving family where she will remain a pet,” Rosenberg says.

-By Cynthia McVey