Cornell Feline Health Center celebrates 50 years of innovation in feline medicine

In 1973, Fred Scott, D.V.M. ’62, Ph.D. ’68, had a vision. What if there were a center focused entirely on the study, prevention and cure of feline diseases? It would be privately funded and support multidisciplinary work by researchers and clinicians throughout the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine (CVM). The young assistant professor sketched out his ideas in a memo to his mentor, Dr. James Gillespie, founder of a new program focused on feline infectious diseases in the Department of Microbiology and gave it the title “A Dream for the Future.”

Scott’s dream not only became reality, but it also laid the foundation for a unique and ever-evolving institution – the oldest of its kind – that is respected worldwide for its work at the forefront of research, education and outreach in feline medicine. This year, the Cornell Feline Health Center (FHC) is celebrating 50 years of improving the lives of cats everywhere.

“It’s very exciting to look at our trajectory,” said Bruce Kornreich, D.V.M. ’92, Ph.D. ’05, FHC’s director since 2019. “We’ve gone from a relatively small initiative originally launched to support the local study of feline infectious diseases to our current status as an internationally recognized center that supports cutting edge feline-focused research in a variety of basic scientific and clinical fields. We provide unique and outstanding educational opportunities for veterinary professionals and the cat loving public. And, we provide support for both of these constituencies through a wide breadth of media, including our recent launch of publicly facing artificial intelligence-based initiatives."

An idea takes shape

“At first it certainly wasn’t on my radar to start a foundation or a center or anything,” Scott recounted. In 1973, he was on the CVM faculty, conducting research and teaching virology to veterinary students. But he had recognized that a large gap existed in small animal medicine.

Until the mid-1960s, very little research had been conducted on cats, as they “were just considered to be a small dog by veterinarians out there,” Scott said. In the past decade, however, some movement had come into the field – especially at Cornell.

In 1964, Charles Rickard, M.S. ’46, D.V.M. ’43, isolated the feline leukemia virus (FeLV) and, in the following year, established the Feline Leukemia Laboratory on Snyder Hill. At the same time, Gillespie started a research program focused on other feline infectious diseases, including panleukopenia, mink enteritis, feline reovirus, herpesvirus, rhinotracheitis, infectious peritonitis and a variety of picornaviruses.

Some of these viruses were beginning to run rampant in cats across the country.

“Suddenly, veterinarians were anxious to get any information about what was going on with these infectious diseases,” Scott recalled.

Having worked with Gillespie on vaccines for panleukopenia in cats – which had a mortality rate of 50 percent at the time – Scott began to address concerned practitioners. “I was traveling all over the country, and I saw that the whole feline area was just beginning to blossom,” he said. Feline Practice, the first journal of its kind, had just been launched, and the American Association of Feline Practitioners had recently been started.

So, when dean Dr. George Poppensiek asked for recommendations on funding programs at the College in 1973, Scott – a member of the General Committee – knew the need for long-term research on cat diseases was clear. Scott believed, though, that funding would be difficult to obtain through the NIH or other large extramural funding agencies. “So, the timing seemed appropriate to launch a comprehensive program to improve the health and well-being of cats,” he said. It could be similar to the Research Laboratory for Diseases of Dogs started by Dr. James Baker in 1951 in that its work could be supported by private donations.

Launching the lab

Cornell’s trustees agreed. In 1974, they voted to establish the donor-supported Feline Research Laboratory (FRL) – the proposed entity did not yet meet the university’s requirements for a center – within the Department of Microbiology.

“It was your idea, now you direct it,” Scott recalls dean Poppensiek telling him. Scott obliged and took up the mantle as the lab’s founding director, a position he would hold for 23 years (and again, briefly, in an interim role from 2007 to 2009). He had no funds for personnel, so he extended invitations to some 25 CVM faculty and staff members with expertise in feline medicine to become “participant members.” Most gladly accepted.

The response from the public – individuals, cat clubs and societies, veterinarians, foundations, corporations and veterinary medical associations – was equally favorable. FRL received a total of $239,632 from contributions, grants and contracts over the course of its first year of existence.

On the move

As support for the lab grew, so did its needs for space and personnel. Initially, members of the FRL conducted their work in various CVM facilities. From his office on the sixth floor of the recently completed Veterinary Research Tower, Scott oversaw the expansion of FRL’s research and its name change, in 1980, to the Cornell Feline Health Center, as he had originally envisioned. A new logo followed a year later, showing a cat and a kitten curled around each other.

Until 1988, Scott remained FHC’s only paid professional. This changed when he hired Dr. John Saidla as a feline extension veterinarian and assistant director. The small animal practitioner from Auburn, Alabama was “a very gifted and talented person,” according to Scott, and also functioned as the College’s director of continuing education. Scott tasked Saidla with starting a feline symposium, now recognized as one of the premier feline-focused veterinary conferences in the world in its 36th year of operation.

When Saidla assumed additional duties within CVM, Dr. James “Jim” Richards took over as FHC’s new assistant director in 1991. With an “easy manner and infectious smile,” as described by Scott, Richards readily took to the job and was a true natural at appearing in the media, “talking about his ‘kitties.’” He was often accompanied by the resident mascots of the Center – first Dr. Mew, a male black-and-white tuxedo cat, and later Elizabeth I, a female calico domestic shorthair. “For many cat owners, he was the face of Cornell University,” Scott said. After Scott’s retirement in 1997, Richards served as the Center’s new director until his untimely death in 2007.

FHC’s offices relocated to the Diagnostic Laboratory in 1995, but the biggest move occurred at the end of 2009. That year, FHC’s administration and laboratories took up residence in a newly renovated suite at the Baker Institute for Animal Health at 325 Hungerford Hill Road – fulfilling a vision Baker himself had described to Scott during the formation of the FRL. “His original concept (was) of an animal health institute composed of a series of centers,” Scott recalled.

As the oldest of the centers, FHC has been “a little bit of a guinea pig here at the College,” Kornreich said. Its philanthropic funding model has served as an example for newer entities, including the burgeoning Cornell Richard P. Riney Canine Health Center and the recently established Duffield Institute for Animal Behavior.

Supporting cutting-edge research

Decades of highly impactful insights into feline health have also demonstrated the benefits of working in close physical and intellectual proximity to world-class infrastructure and researchers across CVM and Cornell.

“This is a very collaborative environment,” Kornreich said. “We have both clinicians interested in feline medicine and basic scientists addressing problems at the molecular, cellular and organismal level – and it’s really unique that these people can directly interact with one another. We provide many opportunities for them to do this.”

Internal grants, in particular, support research financially. Since the year 2000 alone, FHC has awarded over 100 internal grants, amounting to more than $6 million. While the allocated sums were initially smaller and for shorter time periods, the competitive grant program now provides up to $100,000 per year for up to two consecutive years to researchers at CVM for high-impact studies of health issues that directly affect feline welfare. “That’s been really important because it allows researchers to not only acquire the necessary materials to address a particular problem but also to hire people,” Kornreich explained.

Over the past 20 years, more than 80 manuscripts have been published as a result of FHC-funded studies. Topics covered in the studies they describe range from work that has immediate clinical applications – such as how to best prop open a cat’s mouth during a dental procedure to avoid temporary blindness that may occur with inappropriate technique – to important basic scientific studies of feline hormones and viruses. “We really have been focusing on making this program as broad and impactful as possible, addressing problems in as many different organ systems and disease processes as we can,” Kornreich said.

And while the primary focus remains on benefiting cats, “we also understand that, by supporting this wide breadth of different types of research, we may also be able to help other species,” he added. In the 1990s, for example, Margaret “Peggy” Barr, Ph.D. ’91, isolated feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV) from a Pallas cat, an east-Asian species of wildcat. This and subsequent work on FIV significantly advanced the understanding of both the feline virus and its human analog, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Pursuing FIP

There is perhaps no better example of FHC’s scientific impact through the decades than its support of researchers’ work on feline infectious peritonitis (FIP). This life-threatening systemic disease was first described in 1961 by Jean Holzworth, D.V.M. ’50, a pioneer in feline medicine who later served on FHC’s advisory council. FIP develops via mutation of the highly prevalent feline coronavirus (FCoV), which most commonly presents as a benign gastrointestinal infection.

In 1975, FHC researchers decided to launch a major effort to improve their understanding of FIP, develop a diagnostic test, and pursue an effective vaccine. Several graduate students associated with the Center wrote theses on the topic. “This group of scientists did a phenomenal job over a period of twenty years, pushing back the cloud of mystery over this disease,” Scott writes in his autobiography, Open Doors.

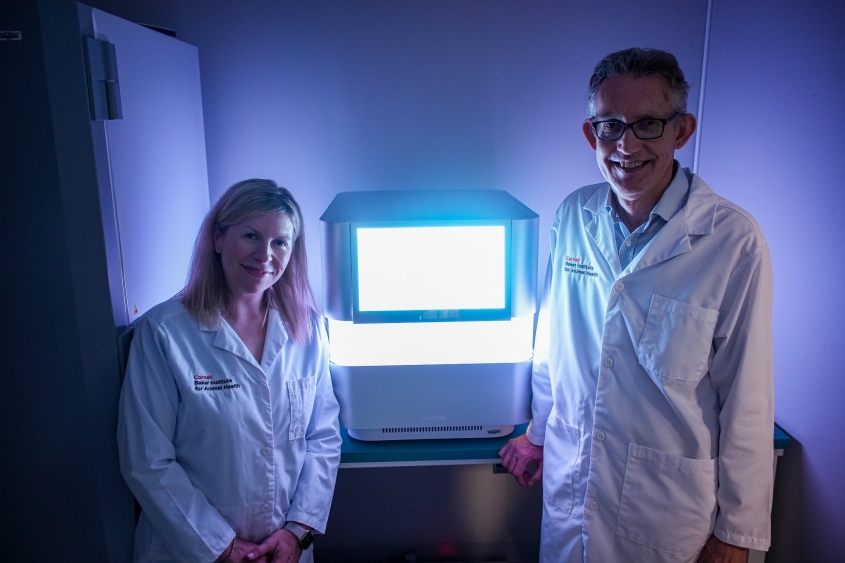

More recently, Dr. Gary Whittaker, the James Law Professor of Virology in the Departments of Microbiology and Immunology and of Public and Ecosystem Health, has used FHC funding to study at the genetic level how the usually relatively benign coronavirus transforms into a highly pathogenic agent. “Dr. Whittaker is a great example of a well-recognized basic scientist who is very interested in clinical problems and in working with veterinarians, people in shelter medicine and owners of cats that have FIP,” Kornreich said. “This work is vital to helping us understand the molecular mechanism of FIP in an effort to identify better ways to diagnose, treat and prevent the disease.”

Thanks to support from FHC’s Rapid Response Fund for a newest-generation sequencer, Whittaker and his colleagues will soon also be able to draw on insights from recent studies to identify specific strains of FCoV and other viruses. “In the case of a future outbreak, we hope we can give clinicians the information they need as soon as possible to respond and contain the emerging situation,” said Laura Goodman, Ph.D. ’07, assistant professor in the Department of Public and Ecosystem Health and the Baker Institute for Animal Health, one of the researchers involved in the studies.

Disseminating knowledge

While supporting cutting edge research on important feline diseases such as FIP is a vital aspect of FHC’s mission, it has also long served as a trusted resource for up-to-date information on feline health to veterinarians and the public alike.

Sue Hostler of South Bristol, New York, for example, credits the wealth of information available through FHC for helping her save her kitten, Henry, who was diagnosed with FIP and ultimately had a full recovery. “If I'd not had access to the knowledge I received via FHC and advice from Bruce Kornreich, I have no doubt I would have lost Henry,” she said. The biotechnology business development consultant has been a fervent supporter of FHC ever since she was impressed with the care she received previously for another cat, Bentley. At age 13 he had emergency surgery to implant a pacemaker, which granted him another six years of life.

From its earliest days, the Center has been keeping both audiences abreast of research findings and practical advice through a variety of newsletters and other publications. The 1983 Felis domesticus: A Manual of Feline Health, for example, was directed at veterinary professionals, while The Cornell Book of Cats: A Comprehensive Medical Reference for Every Cat and Kitten, published in 1989 and updated in 1997, serves as a useful resource for cat owners, breeders and cat care workers.

A multi-tiered membership program provides access to a variety of other perks, including quarterly webinars on topics ranging from surgery to neurology. Most presentations are given by senior residents from the Cornell University Hospital for Animals.

“They are, I would argue, among the most up to date on what is going on in their fields of expertise because they are studying for boards,” Kornreich said.” It also gives them a great opportunity to publicly present and to connect with both veterinarians and cat lovers, both of which are consistent with our educational mission,” he added.

Educating veterinarians

As part of its mission to educate feline-focused veterinary professionals – both those in training and those already practicing – FHC funds resident research projects, which are often showcased at the College’s annual Clinical Investigator’s Day. The Center offers both in-person educational seminars for Cornell veterinary students and virtual seminars for veterinary professionals worldwide. FHC also hosts the annual Fred Scott Feline Symposium, among other unique and impactful veterinary focused educational initiatives.

Since 2003, FHC-funded veterinary student scholarships have supported dozens of students with strong interests in feline medicine, while its support of the College’s Leadership Program for Veterinary Students offers a guided summer research experience to those who hope to broadly influence the veterinary profession through a science-based career.

Reaching out to the public

On the public side, FHC faculty and staff directly communicate with hundreds of people every year to offer them advice and guidance when their cats have health problems – always, Kornreich emphasizes, in concert with their veterinary team. Central to this effort is the Camuti Consultation Service, a fee-based information service established in 1988 on which callers can consult via phone with one of FHCs’ consultant veterinarians.

Kornreich pointed out that “This one-on-one personal touch, through which cat lovers and veterinarians can talk directly with FHC experts, is one of the things that truly distinguishes FHC from other sources of feline-focused health information and support.”

In the 1990s, the Center developed brochures that veterinarians can hand to their clients to inform them on a variety of feline health topics. In 1998, for example, FHC was closely involved with creating revised guidelines on feline vaccines and promptly published a Vaccines and Sarcomas flyer in response to cat owner concerns. Today, the Center offers 25 of these client information brochures that cover everything from how to choose a new cat to management of feline diabetes. Consistent with its mission to reach out to all cat lovers, the Center’s team has begun the process of translating these brochures into Spanish to help veterinarians better serve their Spanish-speaking clientele. Five have been completed and are available on the FHC’s website thus far.

Speaking of websites, much of the information provided by FHC is made available to the public through its website – one of the most frequently visited sites within CVM, with more than 4 million unique visitors in 2023. Email, social media, podcasts and the 2022 appearance by Kornreich in the Netflix documentary Inside the Mind of a Cat further meet people where they are seeking information nowadays. FHC’s newest tool, chatbot CatGPT, even incorporates AI to provide science-based answers about feline health.

The next 50 years

For Kornreich, developments such as CatGPT and initiatives to incorporate citizen science into research are promising signals for FHC’s future. “We have been continuously gaining a deeper understanding of how cats fit into the lives of humans and the environment, and we’re really hopeful and motivated for the next 50 years,” he said.

“As we celebrate what the Feline Health Center has been able to achieve, it is important to remember that we are here thanks to Fred Scott’s vision – and to the continued generosity of our donors,” Kornreich added. “Whether people support us by becoming members or by making donations or bequests, we are so indebted and very thankful to the cat-loving public and veterinary professionals who allow us keep expanding our work and engaging people as partners in our mission to improve the world for all cats.”

Written by Olivia Hall

In celebration of the Cornell Feline Health Center's 50th anniversary, Dr. Scott returned to talk about how the center started, the desperate need for feline research in the 1970s, key people involved in the center's growth, points of pride and more. Take a look at the videos below to hear directly from Dr. Scott.

Humble Beginnings | A Little Room |

|---|---|

Key People | Points of Pride |

Videos by John Enright/Cornell Feline Health Center.