JAVMA: Spike protein may contain key weaknesses in COVID-19 virus

Note: This news item features content from another page. View the featured content for this news item.

Gary Whittaker, PhD, said a shared feature across coronaviruses could be a key vulnerability for SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

Dr. Whittaker is a professor of virology at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine and one of the infectious diseases and epidemiology section chiefs in the Master of Public Health Program. He has studied the proteins, structures, and epidemiology of coronaviruses since 2003, starting with the virus that causes severe acute respiratory syndrome and including the viruses that cause Middle East respiratory syndrome and feline infectious peritonitis.

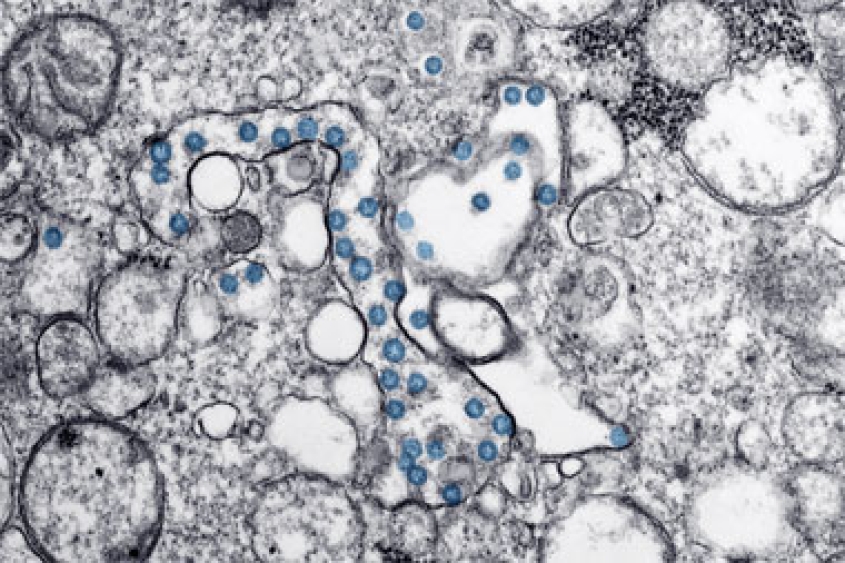

He is focusing his own research on the spike protein coronaviruses use to bind with a host cell’s receptors and fuse with its membrane. Coronaviruses mutate often, especially at that infection site, forming variants and allowing adaptation to new hosts and tissues more quickly than most other pathogenic viruses.

Dr. Whittaker is helping lead a group of laboratories studying the COVID-19 virus, animal susceptibility, or use of existing treatments to combat the disease. Veterinary faculty at Utah State University, for example, led work through the university’s Institute for Antiviral Research to investigate effects of the coronavirus and to test antiviral compounds and licensed drugs that could help people fight the coronavirus, using hamsters modified to be susceptible to infection.

The genetic sequences that encode the COVID-19 virus spike protein that binds with human cells were previously unseen in SARS-like coronaviruses, Dr. Whittaker said. That variation may help the virus spread more easily among humans than the SARS virus—which was deadly but not as easily spread.

Researchers at the University of Minnesota, in an article preview published March 30 by Nature, also indicated they found different mutations that let the COVID-19 virus bind more securely to human cells than the 2002-03 SARS coronavirus. In a university announcement, the researchers described mutations that formed a molecular ridge in the COVID-19 virus’s spike protein, giving it a similar but more compact structure than the one on the SARS coronavirus and letting the virus attach more strongly to human cell receptors.

That work, the announcement states, could guide development of monoclonal antibodies that target the binding site or vaccines that target the spike protein.

Dr. Whittaker said a common mutation in the feline infectious peritonitis virus’s spike protein activation site transforms the virus from one that is highly transmissible but relatively benign to a variant that is lethal but tougher to transmit. The COVID-19 coronavirus, in contrast, has an unusual combination of both transmissibility and lethality.

His research group is looking for key features shared across coronaviruses affecting humans and animals. He sees potential that a drug could target the fusion peptides that become exposed when a coronavirus attaches to a host cell.

“We’re looking at small molecules, peptide inhibitors, antibodies, as well as a kind of vaccine idea to target the activation but really also target the fusion peptide, which is the common denominator for all coronaviruses,” he said.

Such a drug could, in theory, work in the same way as some investigational treatments tested against Ebola virus infection, Dr. Whittaker said.

One coronavirus that causes the common cold is highly related to a bovine coronavirus, he noted, and its emergence in humans has been traced back to a rise in the farming of cattle at higher densities during the 19th century. Another coronavirus of humans, likely originating from a bat in the Middle Ages, may have caused epidemics or a pandemic during that time.

When animals are gathered in close proximity and exhibit high stress—whether in a market, stable, or animal shelter—the viral load builds, he said. Contact with humans during that stress increases the risk a coronavirus will jump species. Stress management and veterinary care can manage that risk and help prevent future outbreaks, he said.

“This is where veterinarians have a major role in human public health,” he said.