Pinpointing elusive, sometimes fatal hairballs in rabbits

After dogs and cats, rabbits are the third most popular domestic pet in both the U.S. and the U.K. Their appeal is obvious: they are cute, furry, smart and playful. They are also mostly self-cleaning. But despite the popularity of rabbits, veterinarians still have a lot to discover about rabbit healthcare.

“There are a lot of conditions in rabbits that are not fully explained,” says Dr. Nicola Di Girolamo, associate professor of exotic pet medicine at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, who also happens to have two rabbits of his own. “We call them syndromes, but with more advanced technology, we can find specific reasons for them.”

One of these puzzling conditions is what’s known to veterinarians as trichobezoars and to others as hairballs (though Di Girolamo clarifies that they’re actually made of hair mixed with ingested food). Most of the time, the hairball will pass through a rabbit’s digestive system without too much trouble, except maybe a few hours of discomfort. Having these transiting hairballs is one of the causes of “gastrointestinal stasis,” though the term is falling out of favor in veterinary medicine since it lacks clarity. Sometimes, however, hairballs get stuck.

That’s where the trouble begins and where Di Girolamo, alongside his Cornell colleague Dr. Christopher Tollefson, assistant professor in the Section for Diagnostic Imaging, began an investigation, the results of which were published in the journal Veterinary Radiology and Ultrasound.

Unlike cats, rabbits can’t vomit, owing to very strong esophageal sphincters. If a hairball gets stuck in the small intestine, it sits, blocking the rest of the digestive tract. Food stays in the stomach and stomach bacteria start producing gas, leading to bloating. The rabbit will stop eating and will become listless. If the problem isn’t treated, it can be fatal.

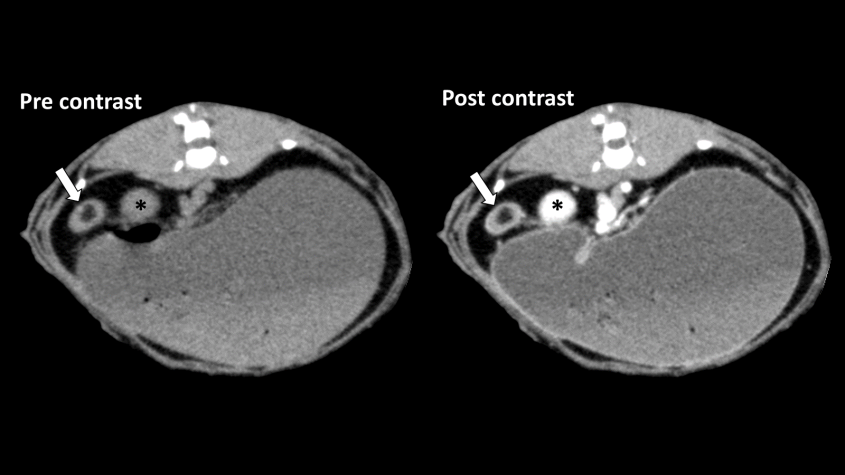

The most obvious way to confirm a hairball would be through some sort of scan. But hairballs don’t always show up on radiographs and it’s difficult to follow the turns and loops of the small intestine on an ultrasound, sometimes making it challenging to find out where, exactly, the obstruction is.

“This creates a lot of frustrations for veterinarians dealing with these fragile creatures and also to owners that don’t know what to expect,” says Di Girolamo. Some of his fellow veterinarians, he notes, say they’ve never seen a rabbit hairball.

Cornell offers CT scans for exotic pets, a category that includes rabbits. With a CT scan, Tollefson and Di Girolamo are able to get more detailed internal images of a rabbit’s intestines.

For their investigation, the two veterinarians took CT scans of seven rabbits at Cornell and two more at Oklahoma State University in Stillwater. All the rabbits showed signs of having hairballs: their stomachs were distended, they had stopped eating and they were lethargic or comatose. The scans showed obstructions with sizes ranging between 86.1 to 633.8 square millimeters at various points in the rabbits’ small intestines.

The researchers found that the CT scan provided many benefits. Six of the rabbits had hairballs in their duodenums, the section of the small intestine closest to the stomach. The remaining three had hairballs near the end of the small intestine. Although not all of the rabbits survived, now that they knew exactly where the hairballs were, their care teams were able to decide a custom treatment plan — surgery rather than conservative management — thanks to the precise, cross-sectional imaging.

Both Di Girolamo and Tollefson are pleased with the results. The CT scan allowed them a clearer look at what was actually going on inside the rabbits and helped them better understand this condition, which has been historically hard to fully comprehend, as well as what they had to do to fix the problem.

More and more clinics across the country are getting access to the type of CT scanners the Cornell team used, says Tollefson, including clinics that specialize in exotic animals. Within five or 10 years, they predict that this procedure will be common for rabbits. The knowledge on this condition built through these cases could be ideally also transferred to other diagnostic methods, such as abdominal ultrasounds, that is currently more widely available.

In the meantime, Di Girolamo advises rabbit owners to pay attention if their pets stop eating. Sometimes a rabbit just isn’t hungry, but if the rabbit seems lackadaisical and its abdomen feels unusually swollen and firm, like it’s filled with gas or undigested food, they should see a veterinarian right away. Force-feeding a rabbit in a case like this can make things worse.

“Rabbits are little puzzles for us to decipher,” says Di Girolamo. “By using advanced imaging, we can find out what’s happening in those rabbits and decipher the puzzle better.

Written by Aimee Levitt