3D-printed bone models help save shih tzu’s leg from amputation

When Marion and Dr. Jeffery Grace brought Coco, their 10-year-old shih tzu, to the Cornell University Hospital for Animals (CUHA) in December 2022, they were determined to save his leg from amputation. Injured severely several years before, the limb had never fully healed and recently gotten worse. “I’m very thankful we came to Cornell,” Marion Grace said. Thanks to cutting-edge 3D modeling and surgical techniques, Coco has not only kept his leg, but is moving normally and happily again.

Six years ago, right after Coco’s injury, even his survival was in question. The tiny shih tzu — then weighing in at a mere 12 pounds — had been attacked by a much larger, off-leash dog near the Graces’ home in Williamsville, New York. “It was just terrible, so traumatic,” Grace recalled. “He had bite marks all over his body, his lungs were punctured, the dog had tried to tear Coco’s leg off.”

Immediate surgery at a nearby animal hospital saved Coco’s life. Follow-up procedures later attempted to repair his leg with bone grafts. But the dog’s bone never fully healed, eventually resulting in failure of all metallic implants — several screws as well as the bone plate and intramedullary pin (a thin metal rod) holding the fracture together. “He was biting his leg and avoiding using it, so he was limping,” Grace said.

The couple decided to bring Coco to Cornell to find out if the limb could be saved.

At CUHA, Selena Tinga, D.V.M. ’12, assistant professor in the Section of Small Animal Surgery, was faced with a highly unusual case. A CT scan revealed that the top and bottom portions of Coco’s bone had not bridged across the fracture, not even with a fibrous union, and his leg remained unstable. “It is rare that we run into this complication – failure to heal and implant breakage — and that the limb has, in effect, been broken for five years while the dog continued to try to use it,” Tinga said.

The bone in question presented a special challenge. “The humerus is almost completely surrounded by muscle, so we had little exposed bone to identify landmarks for limb alignment,” Tinga explained. “It is also encircled by four major nerves, so we had to work between a web of really important structures. If we damaged the nerves, he wouldn’t have function of the leg, and all our efforts would be for nothing.”

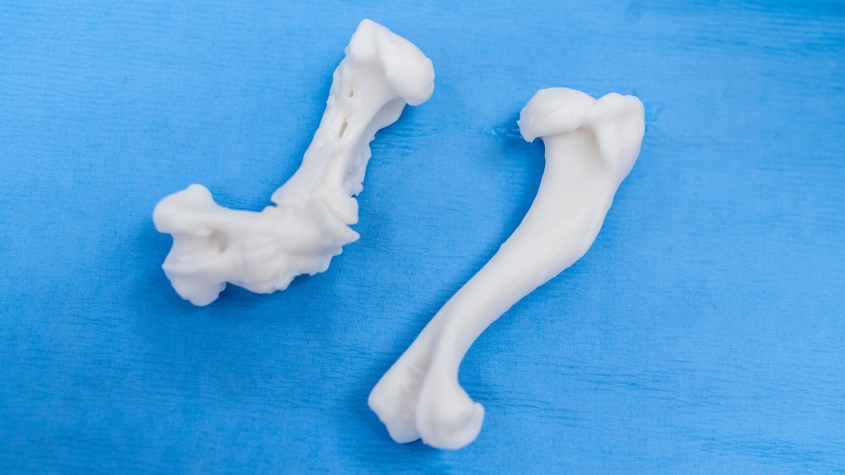

Tinga prepared for the tricky procedure in a time- and labor-intensive process. Using the CT scan and with help from the radiology team, she digitally planned the surgery and created a series of 3D-printed, life-size bone models on which to practice. “It was quite difficult to even understand what was going on,” Tinga said. “The humerus was both bent and rotated at about 90 degrees, and there was a proliferation in the middle where the bone had tried to heal unsuccessfully.”

In the operating room, Tinga was aided by small animal resident surgery resident Dr. Christian Folk, technicians, students and Dr. Manuel Martin-Flores, associate professor in the Section of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, who performed a local anesthetic block and provided general anesthesia. Tinga dissected through the scar tissues that had formed around the fracture and removed the unhealthy bone at the fracture edges. She then affixed custom-made, 3D-printed reduction guides to the top and bottom parts of the bone with pins. The guides interacted with each other in a way that allowed her to move the two halves of the bone back together into a normal shape, despite not being able to see the anatomy completely. Real-time x-ray imaging through fluoroscopy confirmed that the limb was well aligned. Then Tinga applied new bone plates to either side of the bone.

“Without 3D printing technology, we would have had to realign the limb by just eyeballing instead of achieving a near-perfect final shape of his bone,” Tinga said.

Over the next four to six months, Coco’s leg was expected to heal enough to show whether it can withstand future complications, such as implant failure and destabilization of the bone. “Only time will tell if our efforts in the operating room will be ultimately successful,” Tinga said. “Coco may never have a completely normal gait, but my main goal is that he is out of pain.”

Fortunately, at Coco’s latest recheck last summer, he was found to be healing well from his injuries.

More comfortable on his feet, the shih tzu has ventured out into the world with a newfound confidence. In fact, he took his first-ever flight. “Coco did really well,” Grace reported. “At one point, at the airport, my husband had walked him away for a moment. I turned around, and there was Coco, tearing through the airport on all four legs like he’s a superdog! Even though he’s still healing, he looked completely normal. And he’s happy.”

Written by Olivia M. Hall