Rhasaan Bovell's journey in wildlife conservation and cat adoption

Rhasaan Bovell, a doctoral student from Silver Spring, Maryland, is digging into the science behind feline reproduction at Cornell University. A Yale University alum with a background in ecological field research, Bovell's journey now centers on the intersection of biomedical sciences and wildlife conservation.

Bovell's interest in reproductive success in wildlife led him from field research to molecular biology. A two-year stint at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) exposed him to clinical labs and reproductive hormone research, laying the groundwork for his current focus at Cornell.

The unique Biomedical and Biological Sciences program at Cornell, in collaboration with the Smithsonian National Zoo, appealed to Bovell's dual interests, offering a comprehensive Ph.D. experience for those involved in wildlife conservation through reproductive science.

“You can essentially do a Ph.D. that is a 50/50 split between institutions, so you have mentors in both places,” said Bovell.

“It was a perfect fit for my two interests, so the ability to do this program was what brought me to Cornell.”

Part of Bovell's research at Cornell zeroes in on assisted reproductive technologies (ARTs) vital for conserving endangered species, including artificial insemination and embryo transfer. While ARTs are common in places like the Smithsonian National Zoo or other wildlife centers, they often fall short when it comes to feline species.

Bovell aims to understand why these technologies frequently fail, particularly in domestic cats, with the goal of extending the findings to endangered feline species like lions, tigers and cheetahs. More specifically, Bovell has chosen to take a more systematic approach and focus on the feline uterus.

“A lot of people have spent decades looking at maximizing the quality of sperm, eggs and embryos, but there’s a major lack of information about the uterus in cat species undergoing these kinds of procedures,” said Bovell. “What we're interested in seeing is when you have a feline species -- in this case a domestic cat that may undergo these procedures -- is there something going wrong in her uterus or is there some kind of change happening in the uterus during the procedure that’s actually making it harder for embryos to implant?”

Bovell first pitched the research to Dr. Ned Place, Director of the Diagnostic Endocrinology Laboratory at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. The project made its way to Bruce Kornreich, D.V.M '92, Ph.D. '05, DACVIM, Director of the Cornell Feline Health Center and other stakeholders before it was ultimately approved.

Bovell worked with Cornell to find a cohort of cats for his work. “Hopefully, this will eventually help us make more cubs and kittens of some of our endangered cat species in the future. The Cornell Feline Health Center provides a large amount of support for us, and we are really appreciative for the grant.”

Despite minimal prior cat experience, Bovell's close interaction with his feline subjects during the project shifted his perspective. A self-described ‘dog person’ heading into the study, Bovell quickly learned that his personality aligned with the cats with which he was working.

“I realized that cats are incredibly social, affectionate and intelligent,” said Bovell. “They are very creative and crafty, and I totally did not expect that. I thought they were going to be aloof, but they are super-duper playful, so I have warmed up to cats a lot.”

Following the non-terminal, minimally invasive research, Bovell and the facility veterinarians were tasked with finding suitable homes for 20 cats. After spending every day with them for seven months, Bovell slowly warmed to the idea of potentially taking some home.

“I didn't initially go into the project planning to become a cat parent, because I didn't think that I was a cat person,” said Bovell. “Halfway through the study, a few of them had won me over and I knew there was no way that I could leave Cornell without them coming with me.”

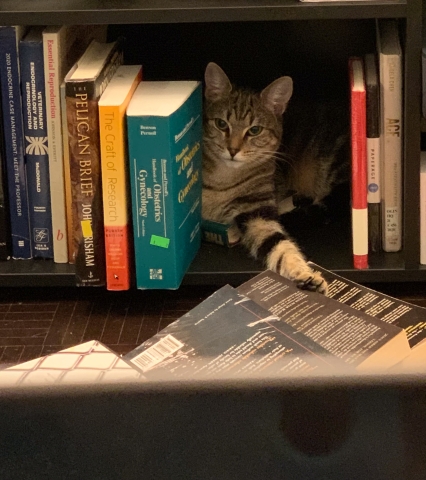

All 20 of the cats used in the project found homes, including the two, 13-month-old cats that Bovell adopted. He affectionately named the pair Rose and Riot, which serves as a nod to their typical feline curiosity and playfulness.

“I took them home from the facility on Halloween, and ever since it's been a bit of a roller coaster,” said Bovell. “It has been so interesting to see how the cats have taken ownership of the space. Watching their personalities change and seeing them learn to engage with the new environment has been so entertaining.”

With the live animal segment of the study complete, the lab work portion begins. Bovell will continue to analyze the data over the next few years and use the results as part of his dissertation project.

As Bovell navigates the midway point of his Ph.D. program following his move from Ithaca down to the Smithsonian National Zoo, his commitment to reproductive science for wildlife conservation remains steadfast. With aspirations to combat extinction through innovative research, he envisions a future dedicated to rebounding declining populations.

“This is the kind of high risk, high value work I see myself doing moving forward, potentially with the Smithsonian if they will keep me after I graduate,” said Bovell. “Fingers crossed.”

Bovell's collaborative work with the Cornell Feline Health Center has not only fueled his scientific exploration but has also led to personal development. It serves as an exceptional example of feline welfare going beyond the laboratory and is consistent with the Cornell Feline Health Center’s mission of improving the health and well-being of cats everywhere.

Written by John Enright/Cornell Feline Health Center