Student blog: Advancing giant anteater conservation in Brazil

What grows up to seven feet long and consumes up to 30,000 ants and termites a day? Their name is quite fitting, as giant anteaters are particularly built to eat this tasty treat with massive claws, a two-foot long tongue, and a jaw longer than their femur. As part of the CVM’s Expanding Horizons International Education Program, I traveled to Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil and teamed up with the two leading institutions focused on the health, ecology, and conservation of Xenarthran species, the superorder including giant anteaters and armadillos. I spent my first month studying free-ranging giant anteaters in the Cerrado savanna with the veterinary team of Instituto de Conservação de Animais Silvestres (ICAS) before joining Instituto Tamanduá at their Pantanal base to participate in the rehabilitation process and post-release monitoring of this species.

Shifting landscapes: Threats to giant anteaters

Giant anteaters in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul coexist in harmony with cattle on integrated crop-livestock-forest farms spanning over 3000 acres each. Landowners are required by law to preserve 20% of their land as a natural reserve for wildlife, with the remainder dedicated to livestock pasture or crop production. The current shift in industry demand and resulting change in landscape allocation toward soybean and eucalyptus production has led to the creation of “ecological deserts,” substantially diminishing the available land for giant anteaters to reside.

In addition to habitat degradation in many parts of their range, unique physiological factors such as dietary specificity, low reproductive rates, and large body size have made giant anteaters particularly susceptible to rapidly spreading grassland fires and road kills. Along highways of Mato Grosso do Sul, the ICAS team recorded over 750 giant anteaters killed by vehicles between 2017 and 2019, making them the third most common victim of vehicle collisions, after six-banded armadillos and crab-eating foxes.

Despite widespread support for conservation efforts, “saving the anteaters” isn’t easy. During my trip, I gained a new perspective learning about the various components of active projects promoting Xenarthran conservation, as well as the bureaucratic hurdles that must be overcome to accomplish change. This species alone has encountered an estimated population loss of 30% over the past 10 years, highlighting the need for close collaboration between veterinarians and wildlife biologists to better understand the health and behavior of giant anteater populations. The goal of my Expanding Horizons project was to gain exposure to every aspect of giant anteater conservation including behavioral surveillance of free-ranging individuals, field capture and veterinary procedures, and care of orphaned anteaters undergoing rehabilitation and after reintroduction.

Adventures with anteaters in the Cerrado

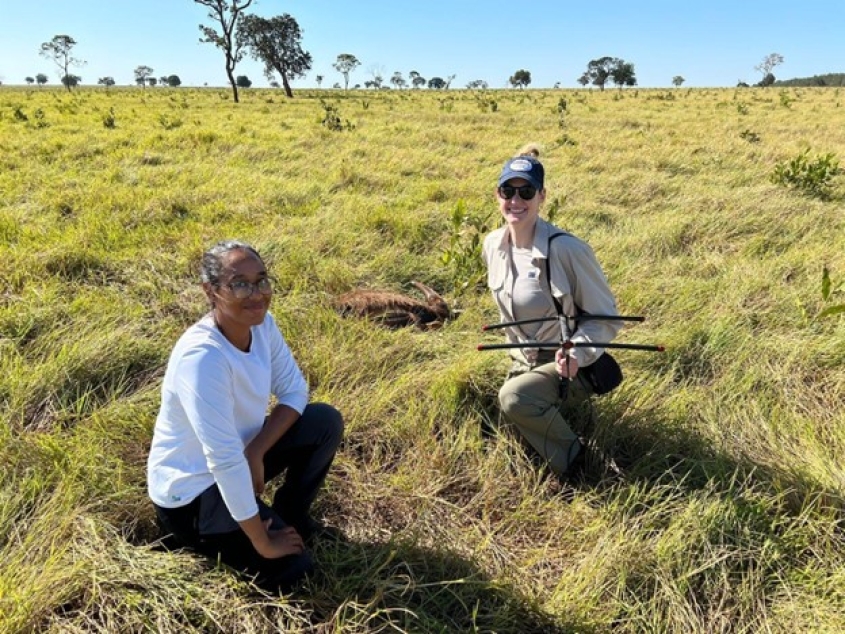

During my first month in Brazil, I joined the ICAS team and worked closely with veterinarians Dr. Mario Alves and Dr. Grazielle Soresini to assess the health of wild, free-ranging anteaters in the Cerrado savanna. We utilized harnesses equipped with GPS and very high frequency (VHF) technology to locate and monitor individuals. These tracking harnesses not only provide valuable spatial distribution data, but enable us to determine how frequently the anteaters cross the road and put themselves in danger. We monitored the 16 individuals with harnesses on one specific farm every two weeks to ensure their harnesses still fit properly, paying close attention to how the leather strap protecting the tracker battery moved as they walked. I have been fascinated by giant anteaters since seeing their mere size in person for the first time at the Naples Zoo a few years ago. It was therefore so special that the first wild anteater I saw in Brazil was Alvinho, a rare albino giant anteater. As we approached his location, the tracker beeping became louder and Dr. Alves whispered, “it’s on five, we’re close.” I didn’t realize just how close until Alvinho appeared from the grassy abyss just a few feet in front of us, his white coat looking more gray now covered in the dust from the Cerrado savanna. As Alvinho scurried away, Dr. Alves explained, “See that leather strap moving? That’s how we know the harness fits right - not too loose, not too tight.” I was also fortunate to arrive at the start of a new long-term research project investigating female anteater dispersal patterns. This required us to survey a new study site, capture new anteaters to collect biological samples, and fit them with tracking harnesses. When not in the field, I was back in the lab processing these samples for shipment to several institutions conducting giant anteater research.

Capturing wild anteaters

Patience and preparation are universal themes when working with any wild animal, but especially when navigating an unfamiliar field site and novel anteater population. During my time with ICAS, I assisted with the capture and sample collection of six giant anteaters and gained key knowledge in the process. For example, prime time for giant anteater spotting occurs as the sun is setting, just as the savanna starts to cool off. During the day the anteaters are sleeping and disappear among the landscape with their giant tails folded over their bodies, protecting them like a blanket. There was also a lot of preparation required, not only to verify the GPS harness was synched and ready for assembly, but that our sedative drugs were drawn up, our sample kits prepped, and vital monitoring equipment charged to ensure a successful and safe capture and release. After the initial injection, we had about an hour to fit the harness, place a microchip, and collect a variety of measurements and samples before moving the anteaters to the wooden recovery box and administering the reversal agent. The sun set quickly so even if we captured them while it was still light out, we often transitioned to headlights mid-procedure and released in the dark. Working with wild animals always keeps you on your toes; no matter how prepared you are, you must also be adaptable. Handling species with unique anatomy also requires some creativity, and during an anteater field procedure two common household items are quite useful: duct tape to wrap their claws for safety and a sock to cover their eyes.

Rehabilitation, reintroduction, and research

For the second month of my trip, I traveled to the Pantanal wetland in southwest Brazil to work with the team at Instituto Tamanduá. My daily routine centered around caring for several giant anteaters in different stages of the rehabilitation and reintroduction process. I learned about dietary needs of young anteaters, enrichment techniques, and the procedure for eventual release of animals back into the wild. Some unique projects included gathering natural enrichment items like termite mounds, preparing for a cold weather event, managing close encounters with curious anteaters, and creating armadillo-proof fixtures to protect the anteaters’ food. I also worked with the biology team to regularly assess anteaters after release via radio telemetry to record their location and compile data on environmental parameters, habitat distribution, body condition, and foraging behavior.

I was surprised to learn that successful anteater reintroductions are in fact very difficult to achieve, and often require multiple recapture and release attempts spanning the course of several months. Many of these individuals have also been raised by the Institute since they were orphaned as pups, resulting in their familiarity and curiosity towards humans. One remarkable experience involved an encounter with a previously released anteater named Cecília, who unexpectedly approached us during a feeding session one afternoon. This interaction and others, showcased the ongoing and complex challenge the Institute is working to address. As my time in the Pantanal drew to a close, I had the privilege of extending my assistance to the veterinary team at Centro de Reabilitação de Animais Silvestres (CRAS), a government rescue and rehabilitation facility partnered with Instituto Tamanduá, where I got to work with multiple native wildlife species including tapirs, toucans, and pumas.

Now back in Ithaca, I am excited to continue on a project started this summer to contribute to the veterinary research database and knowledge of health parameters for free-ranging giant anteater populations. This data once published can be applied to advance the health management of anteaters in zoos, thus improving the quality of life, longevity, reproductive success, and species conservation.

I am grateful to Cornell CVM’s Expanding Horizons Program for their support of this project, and to ICAS and Instituto Tamanduá for their mentorship. It was a privilege to be immersed in the beauty of Brazil and its cultures, and I look forward to building upon the relationships that were established this summer.

Kate Alexy, D.V.M. Class of 2026, is a third-year veterinary student at Cornell University. She earned her B.A. in biology with minors in chemistry and English from Kenyon College. Her professional goal as a veterinarian is to work with both terrestrial and aquatic species, advancing research and clinical care of individuals in zoos and in the wild. Kate has served as the vice president for Cornell’s Zoo and Wildlife society, works as a student technician at the Janet L. Swanson Wildlife Hospital, and aims to educate others as an ambassador for conservation and veterinary medicine as a whole. Outside of vet school she stays active through CrossFit and serves as a volunteer assistant coach for the Cornell men’s swim team.