Study: Veterinary diagnostic labs played key role in COVID-19 response

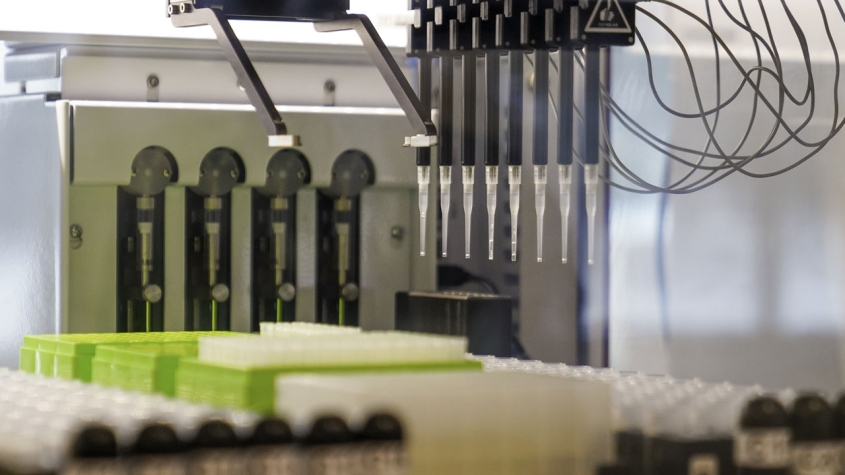

Veterinary diagnostic laboratories across the United States had a substantial positive effect on human health during the COVID-19 pandemic, according to a study from researchers at the Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. The paper, published June 25 in PLOS One, shows the benefits of mobilizing such facilities for population-level testing and timely, informed public health interventions.

“Many veterinary diagnostic laboratories continuously evaluate domestic and wild animal populations for evidence of disease, including diseases that affect humans. They were key in supporting the robust testing capacity necessary for public health agencies to respond to the pandemic,” said Lorin D. Warnick, D.V.M., Ph.D. ’94, the Austin O. Hooey Dean of the College of Veterinary Medicine and senior author on the paper. “We experienced this firsthand through the Cornell COVID-19 Testing Laboratory, established by our Animal Health Diagnostic Center in collaboration with Cayuga Health Systems, a human health care provider based in Ithaca, New York. This paper describes the work and impact of our laboratory and many others across the country.”

As the need increased for severe acute respiratory syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) testing, veterinary diagnostic laboratories across the country rose to the occasion. Some laboratories, however, faced significant administrative obstacles when applying for the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certification required to conduct human diagnostic testing.

“It is important to reduce hurdles before the next major public health emergency. Doing so will enhance access to testing resources overall and ultimately improve population health,” said the paper’s first author Nia Clements, a public health graduate student.

The authors analyzed survey results, interviews and public information. Survey invitations were sent to 76 veterinary diagnostic laboratories conducting SARS-CoV-2 testing on animals and/or human samples, of which 38 (50%) responded. Most respondents (79%) operated within a university. Among the 24 laboratories conducting human SARS-CoV-2 testing, 58% did so for a university population, 29% for the general community and 13% for both. The most common reason for human sample testing was to increase university testing capacity (71%), followed by increasing testing capacity for the local community (25%) and testing to decrease turnaround time (21%). Over 8,250,000 human samples were tested by surveyed laboratories participating in this study.

More than 60% of human infectious diseases have a zoonotic origin, which underscores the urgent need to promote animal and human diagnostic collaboration under the One Health umbrella in preparation for future pandemics.

— Nia Clements, first author and public health graduate student

Some of the university testing programs that offered testing services to nearby institutions and satellite campuses performed a large proportion of their state’s total tests. One laboratory’s daily testing capacity of 18,000 samples corresponded to 20% of all daily testing completed in that state, and to an estimated 1.5–2.5% of all SARS-CoV-2 daily samples tested nationwide. Another laboratory conducted 25% of its state’s total tests, testing four times as many SARS-CoV-2 samples than the state’s public health laboratories and more than any other laboratory in the state.

The authors write that it is imperative for human health agencies and federal regulators to recognize these contributions and readily collaborate with and call on the expertise and resources of the veterinary community and diagnostic centers as new public health threats emerge.

“More than 60% of human infectious diseases have a zoonotic origin, which underscores the urgent need to promote animal and human diagnostic collaboration under the One Health umbrella in preparation for future pandemics,” Clements said.

The contributions of veterinary diagnostic laboratories to the COVID-19 response are an example of how One Health — the premise that the well-being of wildlife, domestic animals, people and the environment are inextricably linked — can serve as a model for the future. For Cornell, a close collaboration with a local human health care provider provided the most efficient path to meet regulatory requirements while benefitting from veterinary diagnostic expertise to establish a high-quality, high throughput laboratory. A hallmark of the program was fast turnaround of test results, which sped up contact tracing and enabled a rapid response from health care providers, according to another study published with the journal Viruses last summer.

By contrast, labs needing to work more independently in some instances faced difficulties in obtaining regulatory approval. Current regulations exclude experience with non-human samples, including animal testing, from the required experience for CLIA certification, posing an unnecessary hurdle for veterinary laboratory participation. For example, according to the study, one state’s veterinary laboratory diagnosticians “were called upon to train human health professionals to perform the testing that they themselves were not certified to perform” as participants in the COVID-19 testing program.

“Ensuring we have swift, efficient mechanisms to respond to the next pandemic doesn’t necessarily mean creating those processes from scratch,” Warnick said. “A One Health perspective helps identify intersections between areas of expertise. It can help save lives, as the work of veterinary laboratory contributions to the COVID-19 response shows.”

Additional authors on the study include Dr. Diego Diel, who led the Cornell COVID-19 Testing Laboratory and directs the Virology Laboratory at the Animal Health Diagnostic Center (AHDC); Dr. François Elvinger, executive director of the AHDC; Dr. Gary Koretzky ’78, vice provost for academic integration, professor of medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine and one of the leaders of Cornell’s COVID-19 response; and Julie Siler, technician in the Department of Public and Ecosystem Health at the College of Veterinary Medicine.

Written by Melanie Greaver Cordova