Endoscopic procedure removes rubber duck from English bulldog’s stomach

Shortly after Charla Nash and her two-year-old daughter Brynlee returned from a vacation to Florida, their English bulldog Maisie swallowed Brynlee’s souvenir from the trip — a little rubber duckie with a pink bow on its head.

“Brynlee took it out of the suitcase and dropped it, and Maisie picked it up thinking it was one of her toys,” says Nash. “I tried getting it out of her mouth, but she refused to let go. When I went to chase her to try to grab it, she swallowed it whole.”

Nash called their veterinarian, who suggested they give Maisie hydrogen peroxide to help her throw it up, but the duckie wouldn’t budge. She then reached out to the Cornell University Hospital for Animals (CUHA). “They were very, very kind and very helpful,” Nash says.

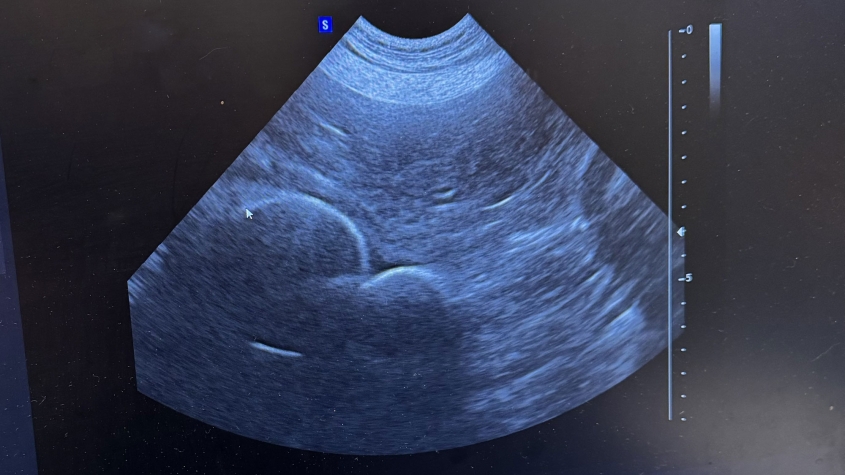

At 10 p.m., Nash made the drive to CUHA from her home in Syracuse, New York. The next morning, Maisie was in under anesthesia for an endoscopic foreign body removal. Fortunately, the duckie was in Maisie’s stomach, which meant it could be pulled safely through the esophagus using an endoscope and a loop. Had it been in her small intestine, she would have had to undergo abdominal surgery, a longer and riskier procedure.

“With dogs who are brachycephalic (flat-faced), we try to go in and be as quick as we can since these dogs are at high risk of aspiration pneumonia and breathing complications associated with anesthesia,” says Dr. Carson Zweck-Bronner, an internal medicine resident at Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine. In this case, an endoscopic procedure would take around an hour, while surgery could take twice as long.

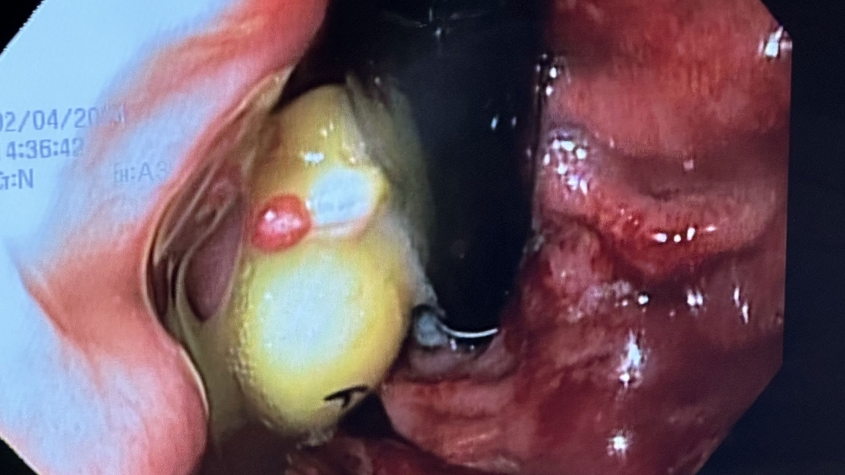

Things became unexpectedly complicated during the procedure, however, when, after 45 minutes of trying to get the duckie, the medical team discovered that it was stuck at the top of Maisie’s stomach. “It was right where our camera enters the stomach,” says Zweck-Bronner. “The duck was directly to the left of the opening. If you can try to picture it, it’s hard to grab an object that's right next to you and not in front of you.” There was also a buildup of mucus in Maisie’s stomach, a common reaction to the introduction of a foreign object, which made the duckie and the endoscopy tools extra slippery.

“We ended up flipping Maisie over to the other side to make the duck fall lower in her stomach, but as we flipped her over, it started to get sucked into her intestines,” says Zweck-Bronner. “We saw it slowly getting smaller and smaller.” If it had gotten all the way into the small intestine, the dog would have had to undergo surgery. “We really try to avoid pulling anything out of the small intestine because you can cause damage to the intestines.”

Finally, at the last minute, Zweck-Bronner was able to lasso the bow on the duck’s head with the loop and pull it out of the stomach. The duck got lodged in Maisie’s mouth on the way out, so forceps were used to pull it out: "A fully intact, cute little girly duck with a little winky face and a bow on top of its head.”

Maisie recovered quickly after the surgery and was able to go home the same day. The hydrogen peroxide that had been used to make her vomit had left her with some ulcers in her stomach lining, so Zweck-Bronner prescribed a medication to help heal them.

As for Brynlee’s collection of other rubber duckies, Nash disposed of them by following a national trend called “ducking,” where Jeep owners will place rubber ducks on each other’s side mirrors. With this in mind, she took the ducks to the mall and placed them on several Jeeps in the parking lot, far from Maisie.

Zweck-Bronner says it’s common for dogs to swallow things they shouldn’t, like underwear, socks, needles and garbage. “We see a lot of other weird things in the stomach, but this was truly my first rubber duck,” she says. “It's a nice win for our team and for Maisie.”

Written by Christina Frank