Ithaca Voice: Breaking down the COVID-19 vaccine with Dr. Leifer

Note: This news item features content from another page. View the featured content for this news item.

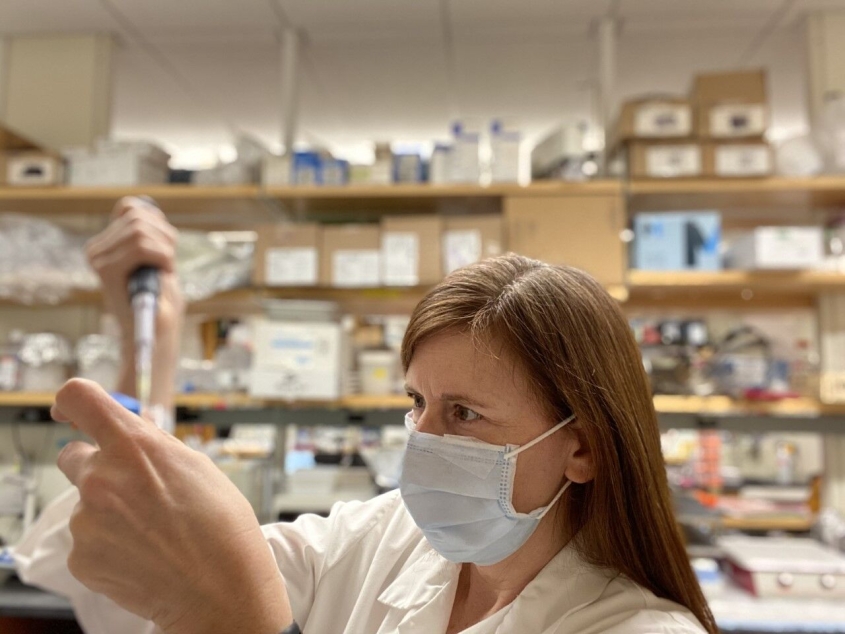

ITHACA, NY -- The COVID-19 vaccine is here, and people have questions. Is it safe? Are there long-term effects? How was it produced so quickly? How long will immunity last? To answer some of these questions, we sat down and talked with Dr. Cindy Leifer, an associate professor of immunology at Cornell University. The cross-disciplinary research in her lab uses immunologic and bioengineering approaches to investigate regulation of immune recognition of pathogens through innate immune receptors, as well as novel types of vaccines that exploit this new information. So yes, she’s an expert.

Part of people’s wariness of the COVID vaccine seems to come from the speed at which it was produced. In under a year, Pfizer and Moderna (and AstraZeneca in the U.K.) had vaccines ready to fight the novel coronavirus. However, Leifer clarified that things didn’t happen quite as quickly as it seems.

“What’s different about this vaccine is a lot of the groundwork was already laid to be able to plug and play,” she said. “Other vaccine manufacturing methods require the growth of large amounts of virus, so it takes a lot of time to figure out how to grow that, package it and test it. But that pre-clinical groundwork was already laid [for COVID-19].”

This makes another important point, and one that is integral to understanding how the vaccine was produced in the timeframe that it was; the COVID-19 vaccine does not use any live/weakened/inactivated virus.

This vaccine is an mRNA vaccine, which teaches our cells how to make a harmless piece of the “spike protein” that is found on the surface of the coronavirus that causes COVID-19. When our cells make that protein, it triggers an immune response inside our bodies, which then produce antibodies that will recognize that protein and fight it to protect us from becoming infected if the real virus enters our bodies.

With that said, mRNA vaccines are not a brand-new concept. Leifer said they have been under study for more than 20 years, but until now none of the other vaccines have advanced to the point of approval. Once scientists were able to get the sequence of the virus for a prototype vaccine, they started clinical trials.

Again, many people have been asking why the clinical trials seemed to happen so quickly. Leifer explained that the way clinical trials work is that you give half of a large group of people the vaccine, half a placebo, and then you wait. You wait until the half with the vaccine gets exposed to the disease to see if it works.

“Usually not enough people get a disease in a short enough time,” Leifer said. “The good and bad of this disease is that it spreads so fast.”

So people who received the vaccine in clinical trials in the different hotspots around the country were exposed to the disease fairly quickly, and the scientists were able to get results in just eight weeks.

“It’s just from happenstance, because this virus is spreading so fast,” Leifer said.

And even though the vaccine was approved through emergency use authorization, the trials aren’t ending, and people who received the vaccines in clinical trials are still being monitored.

“They didn’t shortchange any of the time frames that we need to test the safety and efficacy,” Leifer said. “We could just manufacture it very quickly, and get it into trials quickly, and get it approved quickly.”

Essentially, the process isn’t what’s different — the disease is what’s different.

There have also been reports recently of a new strain spreading throughout the U.S., even as close to us as Saratoga. However, Leifer doesn’t think that will affect the efficacy of the vaccine. She uses a Christmas tree as an analogy; if the spike protein is a Christmas tree and you create antibodies that recognize each ornament on the tree, changing a couple bulbs won’t prevent you from recognizing the Christmas tree.

So now that you know how it’s made and how it works, should you be worried about its safety? Leifer doesn’t think so.

“My personal opinion is I’m not scared,” she said. “They’ve been able to deliver this [vaccine] using lipids that are already present in your bodies […] So should we be scared of lipids that are already present? No. Should we be scared of mRNA? No. Based on the composition of the vaccine there’s no reason to think there should be long-term effects.”

Leifer added that the long-term effects and risks of actually contracting COVID-19 are scarier than getting the vaccine, and that there’s already proof of people suffering from them.

After you get the vaccine you may feel a little yucky, your arm might be sore, you could have a slight fever but frankly, this is a good thing — this is a sign of your immune system working. But other than those mild side effects, you shouldn’t expect any other long-term issues.

As far as how long immunity will last, that’s an unanswered question at this point. There have been reports of people getting COVID more than once (though it’s rare), and some studies have shown that four to six months after someone has COVID, there are no longer antibodies found in their system (though Leifer said it could just be the level the testing is done at).

And though immunity is unpredictable, Leifer said there is evidence that suggests immunity from a vaccine could last longer than immunity from actually getting the disease.

“What we can say is a lot of data from immune responses to COVID shows that the immune response is kind of wimpy,” she said. “People who get the vaccine get a stronger response. So it is possible that it will give longer immunity than a natural infection, but there’s not enough data at this point.”

And she added that even if there aren’t antibodies in someone who had previously had the disease, there should still be memory cells left.

“The reason why vaccines work is because they provide memory to the immune system, and they bank that information so they can recall it really quickly,” she said. “So if you had the disease, the vaccine should boost that.”

For example, when you’re a child you get your TDAP (tetanus, diphtheria and pertussis) vaccine. Then as an adult, you get a booster every 10 years.

“That tickles those memory cells,” Leifer explained. “It’s saying ‘wake up, remember this.’”

Memory cells do differ from person to person and depend on how good an individual’s immune system is. If you’re an immunocompromised person, a baby or a senior citizen, you likely won’t have as good of an immune system as a healthy, younger adult.

“But once you’ve had the disease or vaccine, there will be some memory,” she said. “It might not be a lot, but it’ll be some.”

She added that the vaccine will likely generate better memory in your cells because the virus actually messes with the immune’s system’s ability to generate memory.

“It’s a very crafty, sneaky virus,” she said.

One of the most important parts of stopping this disease is creating herd immunity, Leifer said. When fewer people are susceptible to the disease, the virus can no longer jump person to person. So in this way, vaccines work at two levels to eradicate disease — protecting the individual and eliminating new hosts.

The COVID vaccine has an exceptionally high rate of efficacy at around 95%. This means if you immunize 100 people, about 95 of them will be protected, and in clinical trials there were zero instances of people who got the vaccine getting severe cases of the disease even if they were infected.

As for what percentage of people need to be immunized to create herd immunity, it’s a bit of a moving target. There are variables that are difficult to account for such as infectiousness, mask wearing, physical distancing, etc.

“So we don’t really know,” Leifer said. “Our best guess is 70-85% of people either having it or being immunized [creates herd immunity].”

With Tompkins County’s relatively low infection rates, it means many more people need to be vaccinated.

“We have a long way to go because we’ve done a really good job of keeping people healthy,” Leifer said.

As for if you’ve already had COVID, Leifer said she can’t make a recommendation on whether or not you should get the vaccine.

“There hasn’t been testing or safety studies done on that yet,” she said. “Talk to your primary care doctor and monitor the CDC website.”

Leifer also addressed the issue of vaccinating children. As of right now, the CDC is only recommending people ages 16 and older receive the vaccine.

“It’s mostly an ethical issue with kids,” Leifer said. “They usually require safety and efficacy data at each stage.”

The stages, or age groups, for testing vaccines on children are usually 16+, 16-12, 12-9, 9-5 and so on.

“There are differences between a child’s and adult’s immune system,” Leifer said. “Even men and women have different reactions […] In this pandemic children don’t typically get as severe a disease, but they can pass it along. So it’s important to get it into children’s trials as soon as we can so we can get it to school age children.”

She added that Pfizer is currently working with children ages 12 and up, and will continue moving down in age once everything is proven safe for those children.

And lastly, if you’re wondering which vaccine to get, Pfizer or Moderna, Leifer said there isn’t much of a difference.

“[They] are very, very similar,” she said. “They’re pretty much the same thing. They’re using the same mRNA sequence, the same technology. In my mind, they’re equivalent. My gut instinct is to take whichever one is available first.”

After all, Leifer’s tagline is simple: “Vaccines save lives.”

For the latest information on eligibility and availability regarding the COVID-19 vaccine, check the Tompkins County Health Department’s website (https://tompkinscountyny.gov/health) or Ithaca.com.