Students find optimism in virtual rounds

Spring 2020 was a semester like no other. Over the course of a few weeks, thousands of classes – lectures and seminars, laboratory and performance courses, capstone projects and veterinary clinics – transitioned entirely online. Instructors navigated technical and logistical difficulties, as well as the shifting realities of a global pandemic. But amid the challenges, students and faculty found opportunities for innovation, connection and intellectual growth.

Finding optimism in virtual rounds

When she was struggling because of her learning disability, Lili Becktell kept her spirits up by looking forward to her third year at the College of Veterinary Medicine, when she’d work directly with animals in clinical rounds.

Then, just as clinics were set to begin, veterinary students learned they’d have to leave campus and shift to virtual learning for the remainder of the semester.

“It was a crushing blow,” Becktell said. “When you spend three years in this very, very difficult curriculum, clinics is the light at the end of the tunnel. My learning disability kept me from excelling in the didactic setting, but this is the part of the curriculum where I knew I would shine.”

As students dealt with disappointment, faculty, residents, CVM leadership and support staff raced to adapt a mode of teaching that relies heavily on face-to-face interaction: standing in the same room with the animal and its owner; brainstorming ideas about the animal’s condition with peers; and learning lifelong lessons through the responsibility of caring for an animal’s health and well-being.

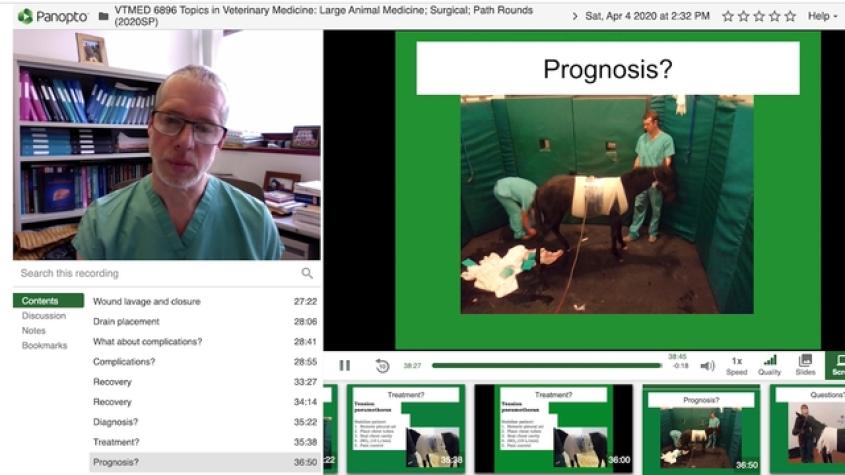

Using a combination of recorded lectures, detailed photographs, notes and videos from past cases, and live Zoom sessions with clinicians in the veterinary hospital, instructors have created a version of virtual rounds to prepare students as fully as possible.

“Incorporating photos and videos of clinical cases was very effective,” said Dr. Rolfe Radcliffe, senior lecturer in large animal surgery, who presented to students about the case of a foal impaled on part of a fence, injuring its thorax and abdominal cavity. “We had really good timelines and a very good documentation for that case.”

Building time for questions and comments for students into Zoom sessions helps approximate the back-and-forth of an in-person conversation, Radcliffe said. Curating past cases exposes students to a comprehensive range of large animal conditions, symptoms and treatments.

The responsiveness of her instructors helped Becktell find optimism, she said, noting that Radcliffe even commented on one of her online discussion posts.

“He said, ‘I know you’re saying that you’re struggling, but what I’m seeing is someone who clearly wants to understand and wants to work hard, and I want to do what I can to make this relevant for you,’” Becktell said.

“It has been really difficult in this virtual medium, but overall the experience has been really positive – if not from the get-go, then definitely trending that way,” she said. “I’m starting to feel hopeful again.”

By Melanie Lefkowitz

A longer version of this story appeared in the Cornell Chronicle.