Simulating amino acid starvation may result in better vaccines for dengue and other infections

Eating a very low-calorie diet is an unpleasant but effective way to live longer, prevent age-related diseases and even improve the immune system’s function. A new study in mice finds that a compound used in herbal medicine can give a similar immune boost if given before vaccination – no dieting required.

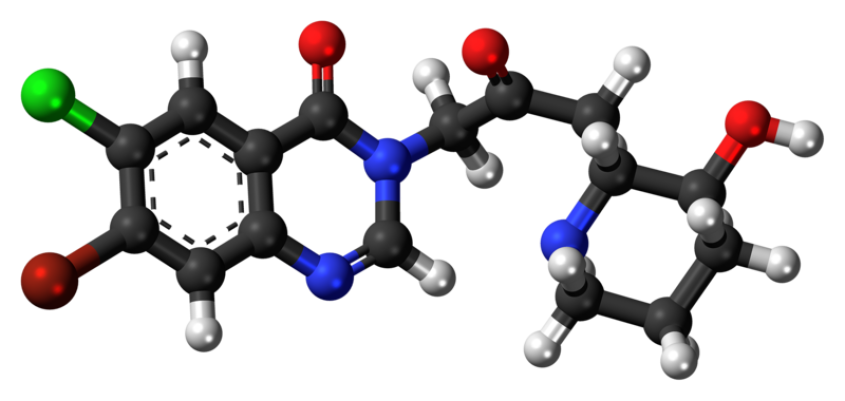

In a new paper in Science Signaling, researchers at the University of Hyderabad in India and Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine show that a compound called halofuginone improves the immune response to a potential vaccine against dengue virus. Halofuginone tricks the body into thinking it is starving for amino acids, which activates a pathway that results in more, and better, antibodies that are better able to neutralizing the virus. With additional testing, the compound could be part of a strategy to improve the effectiveness of vaccines for diseases such as dengue, which have been difficult to control.

The research group was led by Avery August, vice provost for academic affairs and Howard Hughes Medical Institute professor of immunology, and included graduate students Sabrina Solouki and Jessica Elmore, in collaboration with Weishan Huang, adjunct assistant research professor of Microbiology and Immunology, and Nooruddin Khan, assistant professor of biotechnology at the University of Hyderabad in India.

From previous studies, they knew that halofuginone activates a pathway called the amino acid starvation response, which normally kicks in when the body is starved of proteins. Restricting calories can have multiple impacts on the immune system, and the researchers wanted to know how artificially activating this pathway would affect immune response to a vaccine.

“We’ve been studying the pathway using a compound called halofuginone, which is a natural product found in plants,” August said. Halofuginone is a component of an herb used in Chinese medicine. It shows potential for treating muscular dystrophy, autoimmune disease and certain cancers and appears to have few side effects. It mimics amino acid starvation in the body by blocking the enzyme that links amino acids to the molecules that deliver them to the site of protein production.

Members of August’s lab have been experimenting with different mixes of dengue proteins to develop a better vaccine, so dengue was a natural choice for testing the immune effects of halofuginone. The World Health Organization lists dengue among its top 10 threats to global health and about half the world’s population is at risk of contracting the virus. It is transmitted by mosquitoes and causes flu-like symptoms in most people, but in about 20 percent of cases, the infection progresses into severe dengue, which can cause shock, hemorrhaging or death.

The virus has been especially difficult to control, in part, because there is no vaccine suitable for individuals who have not already been exposed. A vaccine developed by Sanofi and tested in the Philippines in 2017 successfully protected individuals who had already been exposed to the virus, but increased the risk of severe dengue in previously unexposed children. Currently, the pharmaceutical company Takeda is testing a new dengue vaccine in a multi-country clinical trial. Initial results are promising, but it is unknown whether the new vaccine will also increase the risk of severe dengue in unexposed individuals.

In the current study, researchers injected some mice with halofuginone and some with an innocuous salt solution, then inoculated all of the mice with a potential dengue vaccine. Then they looked for differences in the immune response to the vaccine in the two groups.

Mice that received halofuginone produced twice as many antibodies against the virus compared to mice that only received the vaccine, and these antibodies bind to dengue viral components more strongly. Mice don’t contract dengue, so the researchers couldn’t test whether they were protected. But when they tested the efficacy of the antibodies against dengue virus in a test tube, they saw that halofuginone resulted in antibodies that more effectively neutralized the virus. “We were particularly surprised by the quality of the antibody response – which is the important part,” August said. “In this case the actual affinity of the antibodies for the virus particles was enhanced by the halofuginone.”

Furthermore, the researchers showed that halofuginone works specifically by encouraging the formation of germinal centers in the lymph nodes and spleen. Germinal centers act like factories to produce the B cells that pump out antibodies, and memory B cells that persist for decades and restart antibody production if the invader returns.

“This pathway hasn’t before been thought of as one that can regulate enhancing vaccine memory,” said August. “It allows us potentially to enhance the body’s memory specifically for that vaccine.”

Halofuginone worked equally well to enhance the immune response against the four types of dengue virus, but this approach likely would boost any vaccine.

Of course, before a shot of halofuginone becomes part of a standard vaccine regimen, the compound will need to be further tested for safety and effectiveness in humans. These experiments used doses of halofuginone that are larger than what people typically ingest through herbal medicine practices. Additionally, the researchers have not yet screened for side effects on other organ systems in the mice, but plan to explore this area in the future.

This study primarily focused on B cells that produce antibodies against invading pathogens, but now August’s group and their collaborators are examining the specific effects of halofuginone on the response of T cells, which detect the presence of invaders, kill infected cells and signal B cells to create antibodies.

Overall, the findings suggest that investigating drugs that mimic starvation may be a promising area of research for finding strategies to enhance vaccine effectiveness, especially for dengue and other diseases that still lack approved vaccines.

-By Patricia Waldron