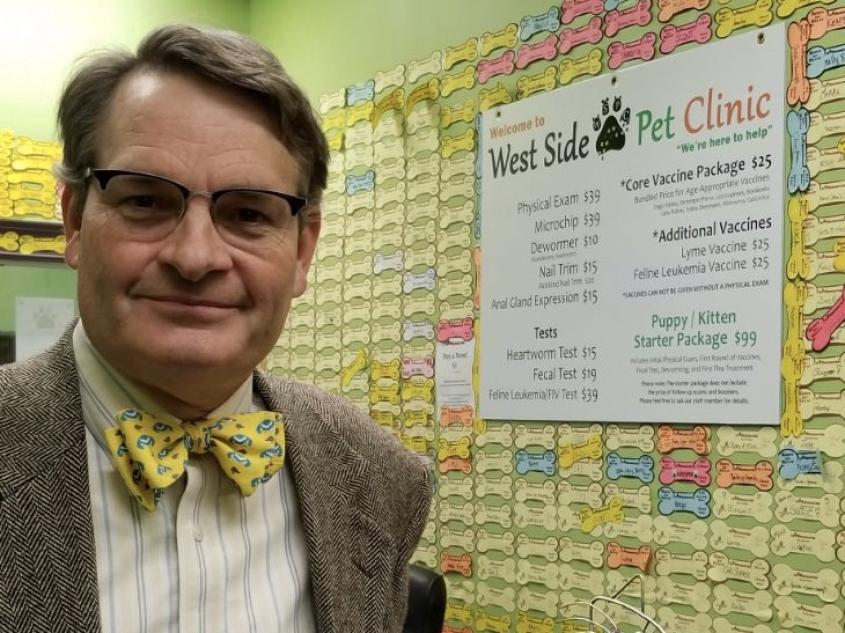

R. Reed Stevens ’85, D.V.M. ’00, opens low-cost clinic in Buffalo

Operating a veterinary practice in Buffalo, which has the third highest poverty rate among the nation’s largest cities, was not an easy proposition for R. Reed Stevens ’85, D.V.M. ’00, when he bought the Ellicott Small Animal Hospital in a downtown neighborhood in 2006.

A native of Buffalo, Reed quickly noticed that the hospital was serving two types of clients: those who wanted the highest level of care for their pets, and those who could only pay the bare minimum to help their pets get by. The first set of clients was spending $250 and up per visit, while the second group would pay no more than $75.

“I started looking at what is the average income in Buffalo, and I said, ‘Wait a second. I’ve got an issue here,’ ” Stevens recalls. “I was trying to run two practices in one.”

Then Stevens had an epiphany while attending services one Sunday at the Westminster Presbyterian Church in Buffalo. The minister was asking the congregants how they could help rebuild the west side of Buffalo, home to increasing numbers of Hispanic, Somali, Asian and Burmese residents. Stevens immediately thought of what he could contribute to the neighborhood: a new clinic for residents who could only afford basic veterinary care for their pets. “The whole idea struck me that it could actually allow me to help my community, solve a problem with my practice as well as reach in and serve people. We could meet them where they are geographically and financially,” Stevens says.

In 2014, the West Side Pet Clinic opened in a former coffee warehouse on Niagara Street and offers a limited number of services at reduced prices: $39 for a physical exam, $15 for a heartworm test and $25 for core vaccine packages for dogs and cats. The clinic, which has not raised prices since it opened, was co-founded by Stevens and Susan Sickels ’77, D.V.M. ’82, a colleague from Ellicott Small Animal Hospital.

The response in the community was so overwhelming that the clinic is moving to a 2,000-square-foot storefront next door that will more than double the size of the practice. Because of the expansion, the clinic would be able to increase the number of exam rooms from two to four and add a lunch room for the staff.

Stevens is thankful to the College of Veterinary Medicine for helping him discover the career that has allowed him to make a difference in the lives of his clients and his community. After graduating from Cornell with a degree in agricultural economics, he spent 10 years working at Nestle Purina and was an international market manager in Taiwan before deciding to switch careers.

While visiting Buffalo for the holidays in 1994, he visited Jim Brown, D.V.M. ’86, his former eighth grade history teacher who had become a veterinarian. “I sat with him in his lobby and it hit me like a ton of bricks,” Stevens says. “This is what you were meant to do.”

His decision was confirmed the first day he walked into class at the veterinary college and his group examined the case of a beagle that had been shot by an arrow. “All of a sudden, for the first time in my life, I had a reason to learn,” he says. “I was learning because in four years, I was going to be asked questions like these.”

Owning a veterinary practice was always a goal for Stevens because of his interest in the entrepreneurial side of the profession. He worked in six different animal hospitals before he bought Ellicott Animal Hospital from Frank Yartz ’69, D.V.M. ’73, the same practice where he had taken his Brittany spaniel and cat as a kid.

As a member of the Veterinary Study Groups, Inc., which provides support to independent practitioners, Stevens attended conferences where industry consultants encouraged the veterinarians to raise prices for their clients and not pay attention to the needs of low-income pet owners. By opening the West Side Pet Clinic, however, Stevens has decided to ignore that advice.

“Running two practices with completely different structures in the same catchment area has its challenges, but we refuse to give up on our lower-end clientele,” he says. “They need help, and in many ways, they need more help than the people who can afford to pay more.”

By Sherrie Negrea